In addition to images, artifacts, and narratives of the history of summer camp, the exhibit includes a participatory digital experience titled Camp Stories, inspired by the popular oral history project Story Corps. The tales collected through Camp Stories will not only be part of the exhibit, but will also be a lasting legacy for students and researchers into the future. Visit Plymouth State YouTube to watch and listen to our “Camp Stories” Oral History Collection.

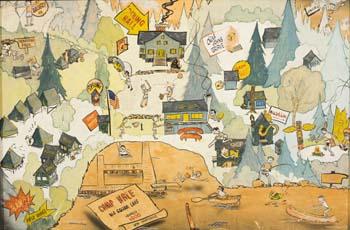

New Hampshire Camps who provided assistance and/ or are featured in this exhibition include: YMCA Camp Belknap, Camp Berea, YMCA Camp Coniston, Camp Deerwood, Camp Hale – United South End Settlements, The Horton Center, Kingswood Camp, The Mayhew Program (formerly Groton School Camp), Maplewood Caddy Camp, The BALSAMS Caddy Camp, Camp Merriwood, Camp Mowglis, Ogontz White Mountain Camp, Camp Onaway, Camp Pasquaney, Camp Pemigewassett, Pierce Camp Birchmont, Camp Sentinel, and Camp Winnetaska.