On Tour March 3, 2010 - February 29, 2012

Multiple Locations

Project Director: Dr. Catherine Amidon

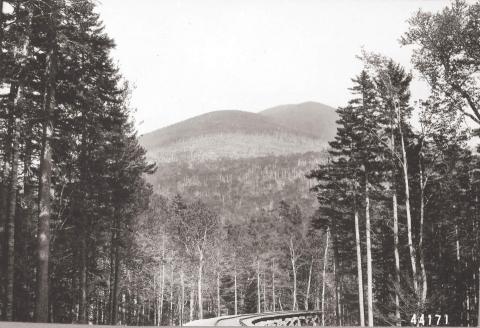

Efforts of the forest advocates succeeded in creating a national movement, resulting in the passing of the 1911 Weeks Act. The White Mountains and its forests were saved. Today there is a wealth of photographs, personal accounts, and calls for action that demonstrate the efforts of the forest advocates, the original beauty of the White Mountains, and the negative effects of unsustainable practices on the environment, landscape, and local communities.

The 1911 Weeks Act created a truly national forest system, authorizing the federal government to purchase and maintain land in the eastern U.S. as national forests. Neither federal nor state governments owned any substantial forested lands east of the Mississippi. Where mountains and forests met, tourist, timber, hotel, railroad, mining, textile, and agricultural groups competed to have the land meet their needs. The discussion grew contentious: Was it constitutional for the government to purchase private lands for public conservation purposes? What impact would the purchase have on both the economic and physical environments of the region? Was scenery of value?

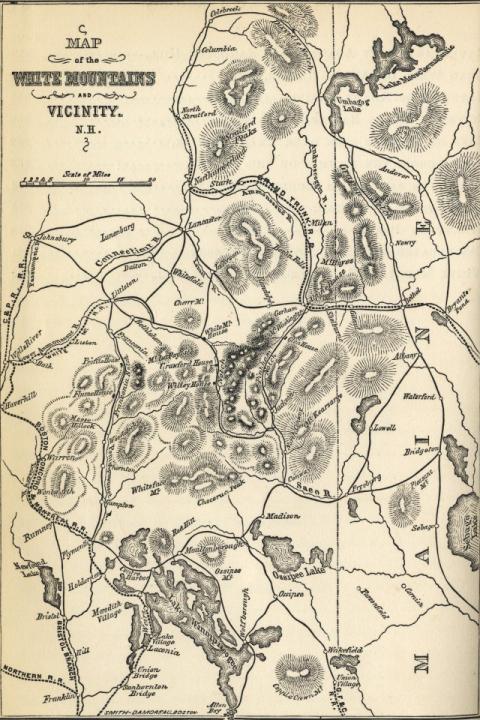

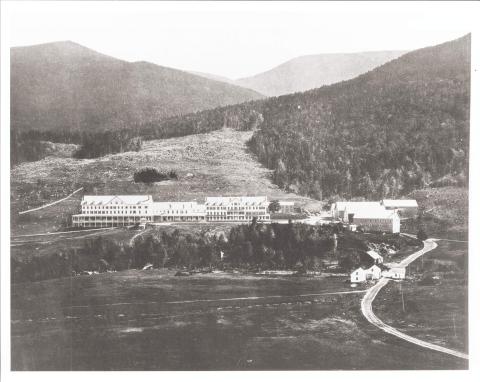

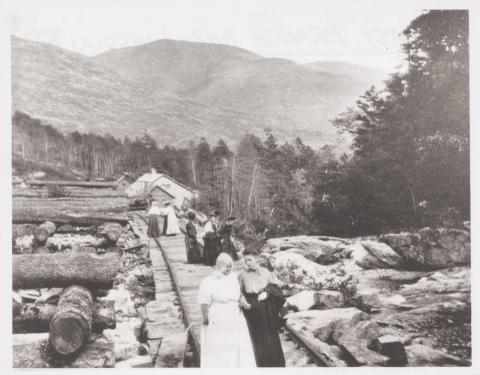

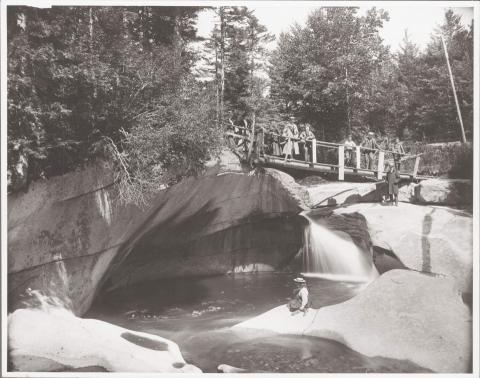

In the mountains of New Hampshire, the arguments met reality. Tourists and hotel proprietors discovered the region by the 1830s, while the timber industry and the railroad moved in largely after the Civil War. For tourists, the White Mountains were a refuge from the industrial chaos of the cities. It was, of course, that chaos which provided the financial means for upper- and middle-class tourists to explore the mountains and for hotel owners to build hotels with increasingly sophisticated amenities to house them. None of the industries were sustainable as they were practiced in the late nineteenth century. From the late nineteenth through the early twentieth centuries, a widening group of mountain forest advocates employed utilitarian and aesthetic reasoning to protect “their” White Mountains.

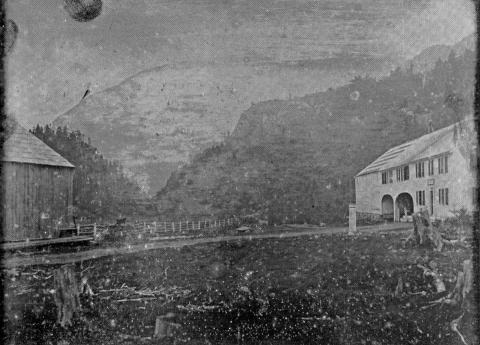

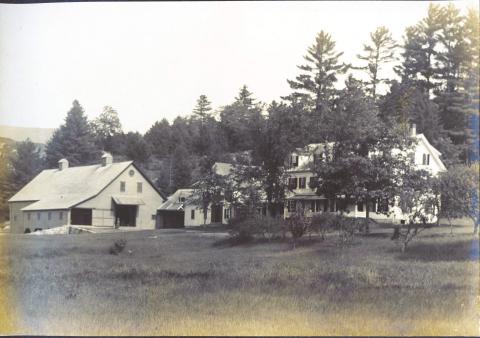

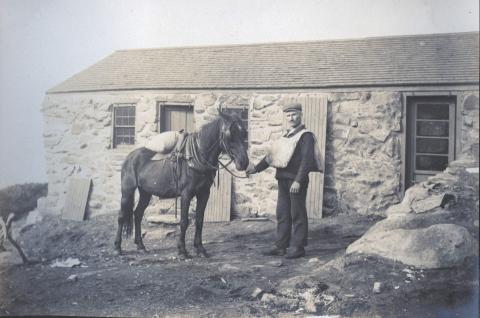

The first inn of the White Mountains was a rough tavern built in 1803 by Eleazar Rosebrook. His descendants in the Crawford family worked their farms, constructed roads, and accommodated travelers in what was soon known as Crawford Notch. By 1819, the Crawford inns were along “the principal, if not the only, market road then traveled by the people…from the upper part of New Hampshire, and even west of Vermont.” Travelers began to look for ways to experience the beauty of the mountains. In 1819, Ethan Allen Crawford and his father Abel cut a path to the top of Mount Washington and in 1827 they widened the path for those on horseback. “It was advertised in the newspapers, and we soon began to have a few visitors.” This marked the beginning of the scenic tourist trade.

A wide variety of people traveled from far and wide to visit the area. In 1832, Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote, “Ethan Crawford’s guests were of such a motley description as to form quite a picturesque group, seldom seen together except at some place like this, at once the pleasure house of fashionable tourists and the homely inn of country travelers. Among the company at the door were the mineralogist and the owner of the gold opera glass whom we had encountered in the Notch; two Georgian gentlemen, who had chilled their southern blood that morning on the top of Mount Washington; a physician and his wife from Conway; a trader of Burlington; and an old squire of the Green Mountains; and two young married couples, all the way from Massachusetts, on the matrimonial jaunt. Besides these strangers, the rugged county of Coos, in which we were, was represented by half a dozen woodcutters, who had slain a bear in the forest and smitten off his paw.”

American writers and painters also flocked to see the spectacular landscape. They taught Americans to value, and even treasure, the forested White Mountains. Word spread of deep valleys, high mountains, and broad open intervals hidden deep in the White Mountains. It inspired a romantic response in the many tourists. In 1832, Nathaniel Hawthorne observed that the mountains: “are majestic, and even awful, when contemplated in a proper mood, yet, by their breadth of base and the long ridges which support them, give the idea of immense bulk rather than of towering height. Mount Washington, indeed, looked near to heaven: he was white with snow a mile downward, and had caught the only cloud that was sailing through the atmosphere to veil his head.” The land had become landscape.

As New England farmers left the area for Midwest farmlands, the White Mountains grew increasingly popular. Fabyans, the Lafayette House, the Flume House, and many other increasingly comfortable hotels sprang up throughout the region.

Tourists clutching their guidebooks traveled by railroads to the Whites beginning in the early 1850s and more followed. Popular among urbanized New Englanders and New Yorkers, the tourist industry promoted the Whites as a place for quiet rejuvenation and contemplation.

Tourists were not the only ones who were inspired to head to the mountains: news of tall trees brought loggers. More and more land was sold to speculators—both to benefit tourists and to benefit loggers. The State of New Hampshire sold off the remaining public lands, including Mount Washington, in 1867 for $25,000. Soon thereafter, all White Mountain real estate was in private hands. Hotels sprang up as the sound of saws penetrated deeper into the forests.

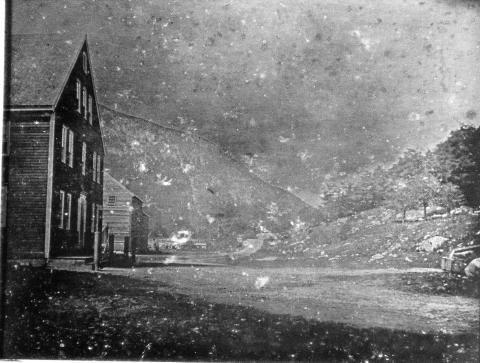

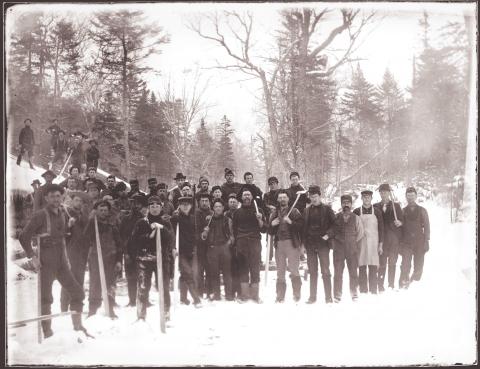

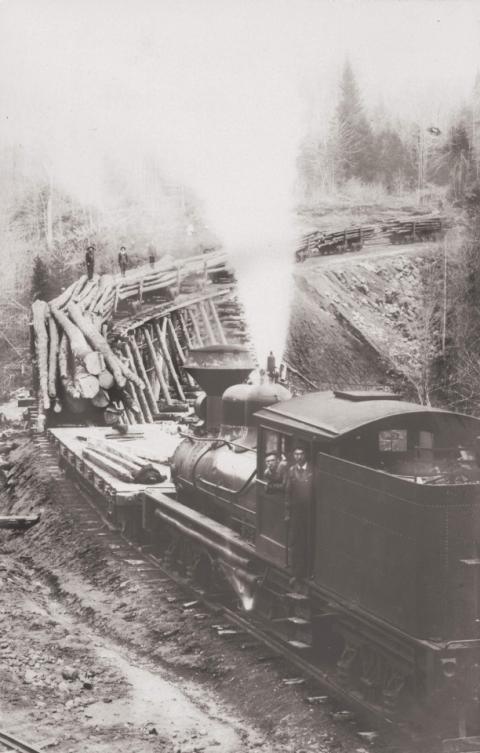

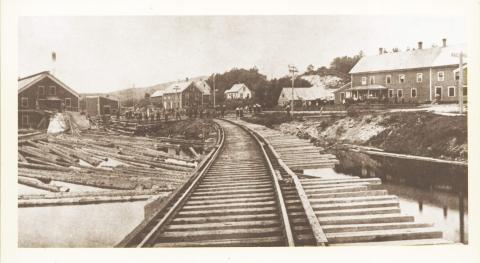

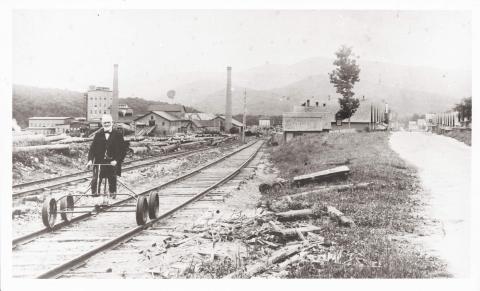

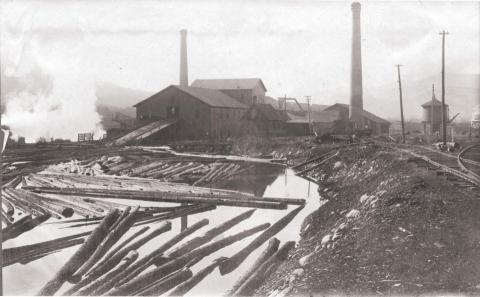

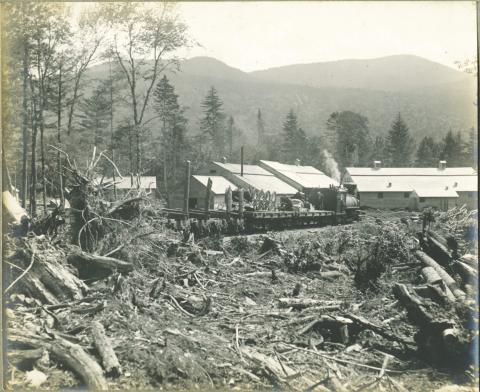

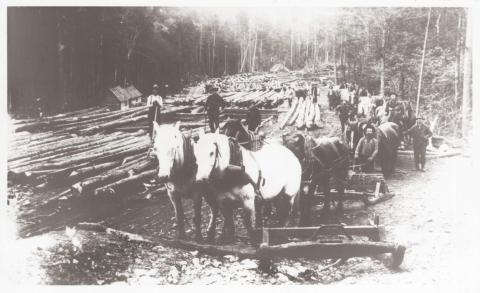

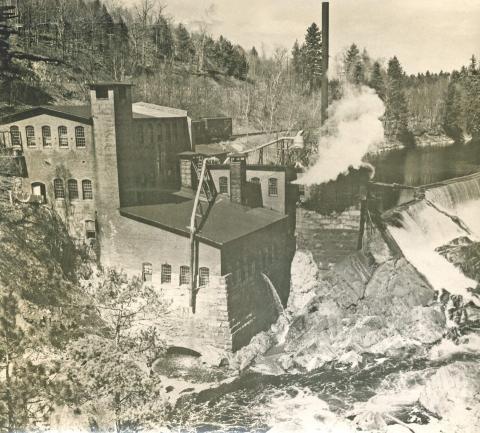

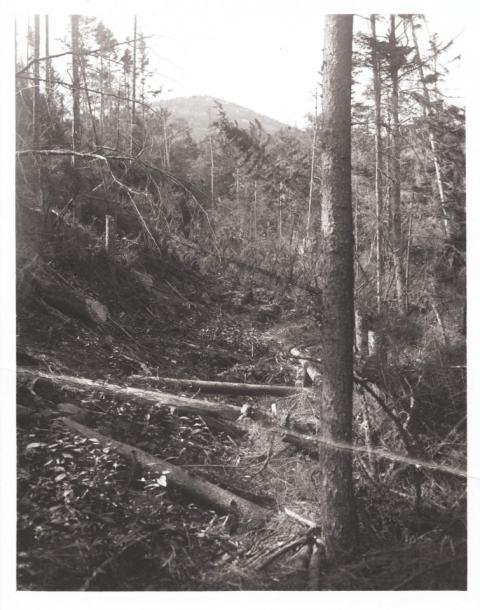

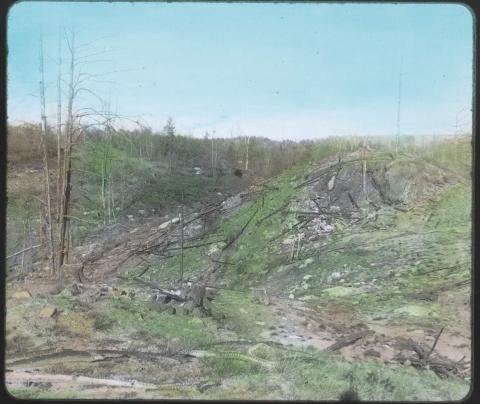

After the Civil War, logging railroads penetrated previously inaccessible mountain regions. A more significant change, however, was the development of a new chemical process that enabled papermakers to make paper from softwood trees. Suddenly softwoods, especially high-altitude spruce, became valuable. Large-scale logging operations clear-cut huge swaths along steep mountain slopes.

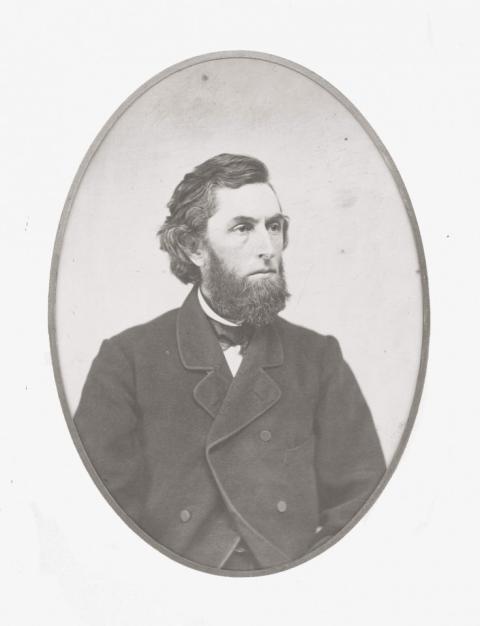

Early in this process, Concord, New Hampshire resident and member of the state’s first forestry commission, Joseph B. Walker spoke out.

What can we do to avert the dangers that impend, for I hold that we cannot afford much longer to do nothing? … We are drifting towards a timber famine.

He called for a “thorough survey of all our forests, making known to us their varying characters, condition, and situation.” Walker was in step with outdoor enthusiasts and academics from Boston who founded the Appalachian Mountain Club in 1876. As they focused on building trails and enjoying the White Mountains scenery, they too became alarmed as loggers stripped valleys and began working on the sides of their favorite mountains.

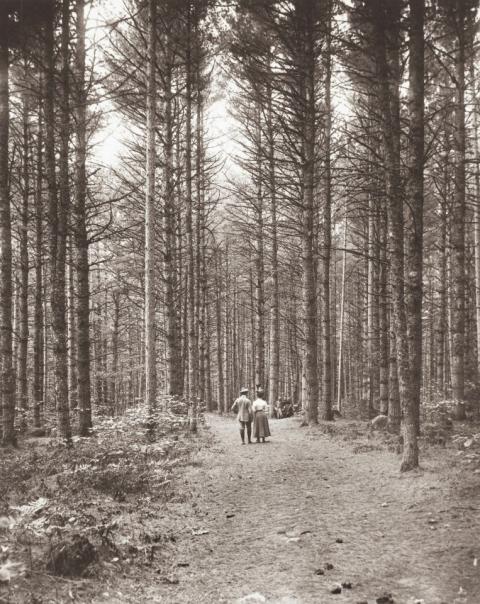

Some of the more permanent timber companies, particularly the Berlin Mills Company (later Brown Company) in Berlin, New Hampshire, recognized early on the need for the implementation of forest management practices and the need to “preserve the scenic value” of the White Mountains. In 1894, Berlin Mills Company hired forester Austin Cary of Bangor, Maine, as a forestry consultant.

According to the company’s records, Cary was the first private forester employed in the United States. Cary and subsequent industry foresters laid the groundwork for New Hampshire’s sustainable forestry management initiatives. Sustainable forestry was a method used to “save such trees as are not [of] sufficient maturity to render them commercially valuable or which are so placed as to give no hope for their immediate reproduction in case of removal, or which ought not to be removed by reasons of their consummate value in the relations they sustain toward the scenic and economical interests of the commonwealth.”

Berlin Mills Company officer William Robinson Brown spearheaded the company’s forestry management practices. Brown was also critical of the increased use of portable sawmills in the White Mountains. Quoting Joseph B. Walker, Brown wrote that such sawmills “cut the forest clean like locusts.”

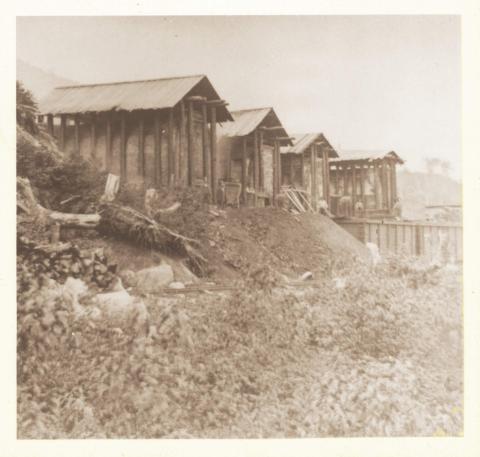

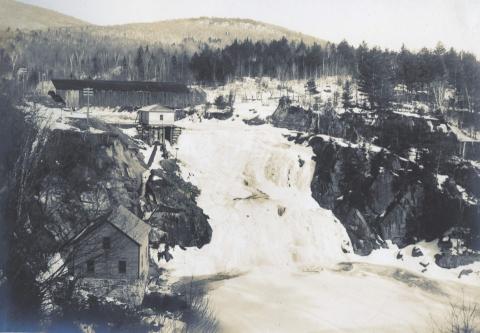

Other logging operations became infamous. In the 1880s, J.E. [James Everell] Henry & Sons controlled and devastated a 10,000 acre tract in the Zealand Valley. They created a logging town in the early 1880s which included not only a mill and railroad (to get the logs to the mill) but also workers’ housing, a post office, a store, a school, a depot, and even charcoal kilns—used to gain the last full measure of value from the timber of Zealand Valley.

The beautiful Zealand Valley is one vast scene of waste and desolation; immense heaps of sawdust roll down the slopes to choke the stream and, by the destructive acids distilled from their decaying substance, to poison the fish; smoke rises night and day from fires which are maintained to destroy the still accumulating piles of slabs and other mill debris.

“The Trail of the Sawmill,” editorial, Boston Transcript, Wednesday, July 20, 1892

By the late 1890s, J.E. Henry & Sons had taken all available timber from the valley and the town disappeared. The company moved next to Lincoln and repeated the process, moving deeper into the forest and higher into the mountains.

In the wake of such extensive cutting, forest fires were inevitable. The mountain forests appeared in danger of annihilation. What could be done to save them? How could the seemingly competing goals of logging interests and conservationists be reconciled? As New England essayist Bradford Torrey asked, “Who thinks of sympathizing with a tree?”

I never see the tree yit that didn’t mean a damned sight more to me goin’ under the saw than it did standin’ on a mountain.

Quote from one of J.E. Henry’s sons. C. Francis Belcher, Logging Railroads of the White Mountains (Boston: AMC, 1980), 131.

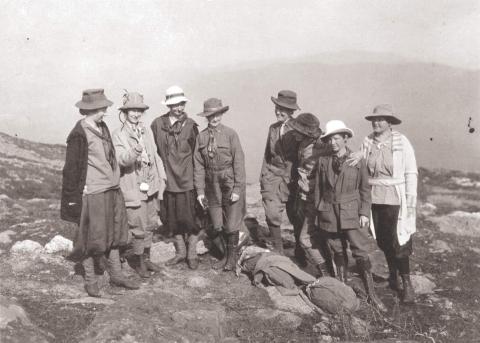

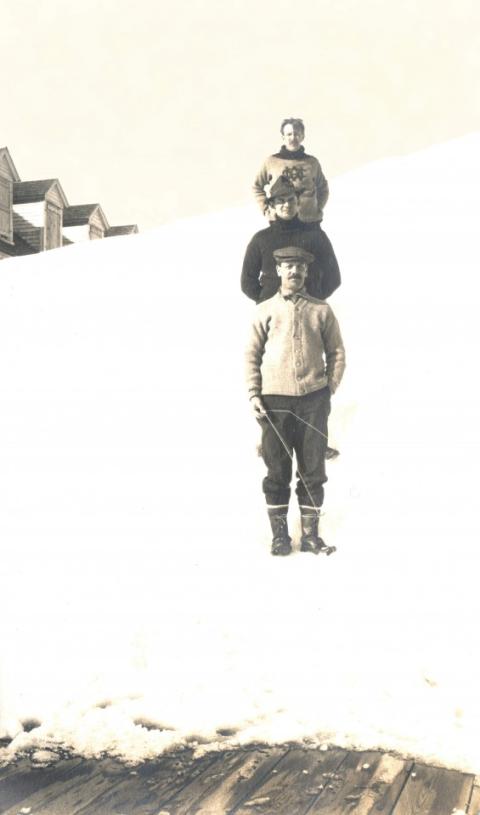

As the loggers moved deeper into the White Mountains, tourists continued to arrive. Some tourists stayed in the increasingly grand hotels, such as the Mountain View House, but many stayed in farm houses that were turned into small boarding houses such as the Mountain Park House or the Philbrook Farm Inn. After being “whirled along in the smoky rattle and roar of the railway journey,” as AMC member and Framingham, Massachusetts resident Isabella Stone wrote to a friend in 1882, some tourists stayed near their hotels, venturing out only to take part in nearby hotel activities, but the more intrepid hikers went much farther afield. They took part in hikes to find grand views and in trail-building activities associated with the AMC.

Not all welcomed the new type of tourist: a reader in the Boston Traveller wrote:

“We are disgusted with the arrogant claims of educated tramps and ‘culchowed’ [cultured] pedestrians who have set up a sole-leather aristocracy, insisting that nobody can ‘do’ the mountains except under the aegis of the Appalachian Club, or on foot, alone with scribe and staff, wallet, hammer, and impaling needles.”

There was tension even among tourists. Surprisingly, even as tourists complained about fires, they also hoped to keep the mountain tops clear so that they could enjoy the views, even if that meant cutting or burning trees. Isabella Stone wrote to a friend from New York who was traveling to the mountains: “the view from the summit is indeed beautiful and one must regret its already evident obstruction from the rising tops of a forest of young growth.” In 1881, AMC member Marian Pychowska wrote to a friend that the top of Mount Kineo “has not been done as thoroughly as I hope it will be one day (not [yet] by fire).”

Logging continued without restriction as the pulp mill industry slipped into high gear during the 1880s. Clear cuts became the norm because pulp mills could use trees of all sizes. The fires that followed the woodsmen left behind a blackened, gnarled landscape. 1886 was a watershed year: more than 12,000 acres were burned in the Zealand Valley. On July 7, 1886, Marian Pychowska was hiking just off the Davis Path when she noticed a fire. “Earlier in the day we had noticed the smoke that rose from behind Mount Franklin. Now it had filled Crawford Notch and drifted way round to Conway, while great yellow-brown volumes rolled up from the increasing fire, making the southern landscape all lurid.” The fire was still raging on July 16 when George N. Cross recorded in his diary:

All day great volumes of smoke have been rolling up from a mighty forest fire on the other side of the Carters in the great wilderness. Tonight there is a lurid light above the treetops. Only rain will extinguish this fire.

The smell of smoke reached the state capital and ashes covered the drying laundry in Manchester. After the 1886 fires, “public opinion moved slowly toward a conservationist view, not only among summer visitors but [also] within the state.” During the 1890s, there were up to 800 fires a year. All concerned with the long-term vitality of the White Mountains called for change.

In 1864, Vermonter George Perkins Marsh made a connection between forests and watersheds in Man and Nature. Evidence of this was seen later in New England. In October 1896, the New York Tribute reported that “T. Jefferson Coolidge, treasurer [and manager] of the Amoskeag Cotton Mills, Manchester, NH, … [advised] that losses in the mills along the Merrimac River resulted, in part, from the great freshets of April 1895 and March 1896 which disrupted plant operations. The lengthy shutdown of the Manchester operation idled 6,000 workers. Both actions resulted from the cutting of forests around the headwaters of the Merrimac, Pemigewasset, and their tributaries.” Based on Marsh’s work, advocates understood that forests retained rainwater and released it slowly. Without a forest cover, there would be increasing spring floods and fall droughts. Marsh’s work influenced all later movements to preserve lands and heralded the beginning of a modern understanding of ecosystems.

In 1885, the first New Hampshire Forestry Commission reported that New Hampshire forests were “a public resource.” “To recklessly destroy [the forests] is as unwise as to throw away any other natural resource which may be conducive to the welfare of the state.” But the same group reported in 1893 that “all the mountain forests in New Hampshire are private property, and … we have no more control over them than we have over the condition of life on the moons of Mars.”

During the 1880s, Joseph B. Walker began to push what was then a radical idea: government purchase of private lands in the White Mountains to create a “public forest.” In an address to the Fish and Game League, he suggested, “the purchase, at low and established prices, by the state, of some of the denuded areas recently cut over, to be held and managed hereafter as public forests.” In 1892, the same year New York created a park in the Adirondacks, Walker asked New Hampshire to accept donations of land for preservation. But, hampered by a lack of funding, the state legislature did little: it passed a few forestry laws, created some temporary forestry commissions, and, in 1893, established a permanent forestry commission.

The value of the New Hampshire timber harvest doubled in the 1890s. In an 1893 article in the Atlantic Monthly, Julius H. Ward wrote that there had been a:

frightful slaughter of forest, the trees cut off entirely … and that what ought to be enchanting scenery along a great railway has been ruthlessly laid waste by the lumbermen and by fire.

The argument seemed to be that the state could either promote tourism or promote timber and pulp interests. “It is plain that in the future, if these great domains are to be maintained in their substantial integrity and wholeness, there must be some other arrangement for their protection and preservation than now exists, so that the charm of the region as a great national park may not be lost, and the rights of private owners, who have purchased this property in good faith and are entitled to revenues from it, may be preserved. The question is, What shall this protection be? and it is more easily asked than answered.”

Pushing voluntary cooperation for forest management had minimal impact. Urging the state to buy the region would not work; the state could not afford to purchase even a small portion of the White Mountains. Congress refused to consider creating a national park. In 1892, North Carolina geologist Joseph A. Holmes offered a new idea: instead of a park, why not create eastern national forests to match the new western ones? New Englanders agreed. “The demand exists that the White Mountain region shall be in some way regarded as public property…. New Hampshire enjoys the unique distinction of having a domain which nature has pointed out for a great public park; not a sportsman’s preserve… but a people’s hunting and tramping ground, where the domain is as free as the air, and where every American feels that the endowments of nature are as permanent and secure as the Constitution.” But was it constitutional for the national government to purchase private forest lands for public purposes?

Advocates found the spark that would ignite the general public’s interest with the publication of the Rev. John E. Johnson’s rather lurid tale of The Boa Constrictor of the White Mountains; or the Worst Trust in the World in 1900. “Summer visitors to this section of the White Mountains have noticed the many deserted farms and dilapidated buildings and have wondered at such scenes, not dreaming that the cause was to be found in the operations of a company chartered to do it; that this desolation was due to the gradual tightening of the coils of a boa constrictor legalized to crush the human life out of these regions, preparatory to stripping them of their forests.” He blamed George James’ predatory New Hampshire Land Company, a large and rapacious timber company. “What is its object? To deforest and depopulate the region lying around the head waters of the Merrimack River in the heart of the White Mountains.” He asked that both state political parties unite “in an attempt to crush such an unmitigated outrage upon the rights of humanity.”

The New England Homestead, a magazine found in the home of almost every New England farmer, spread the news and let readers know that:

The state of New Hampshire is facing a crisis. The destruction of the forests has reached a point where the very source of her wealth and the most potent factor in the economic life of her people is threatened a blow beyond reparation. She is in the grip of the lumbermen and land speculators, and whether or not she will free herself is of vital concern, not only to herself but to the great manufacturing interests centering along the Merrimac river in Massachusetts and to that vast body of people at large who turn to the White Mountains in quest of health and recreation.… Talk alone cuts no figure. The lumber barons are united as one man. The vast public, if united as one man, can easily secure justice. Protest, long and loud, is well enough, but let us organize so as to make protest effective. … Instant action is imperative.

The next week, the Homestead printed a membership application “To save New England’s farms, homes and industries” and the editorial column was full of letters of support. The public was solidly behind the project.

In early 1901, supporters created the Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests [SPNHF]. According to its constitution, the group’s primary objective was “To preserve intact the scenic beauty in selected places throughout the state where the forest is an essential element, particularly upon the high and steep slopes in the mountains.” Farmers, bankers, ministers, surveyors, editors, legislators, foresters, members of women’s clubs along with corporate, government, and civic leaders; and even the head of the Berlin Mills Company supported the new association.

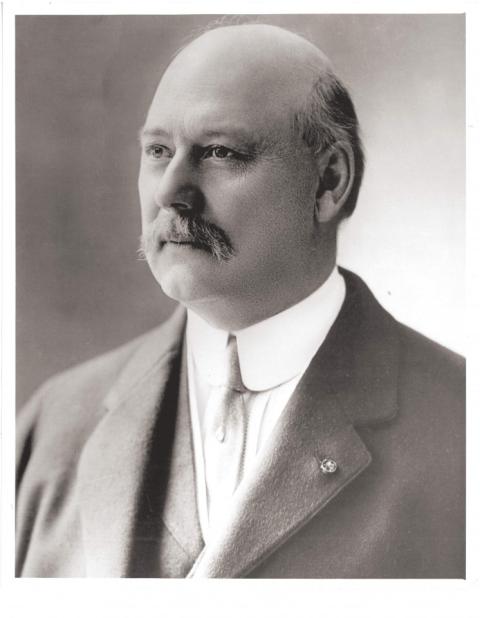

In late 1901, SPNHF hired 41-year-old history PhD, social worker, and newly-minted forester Philip W. Ayres to be its forester, publicist, and manager. Ayres accepted the job on one condition: that the SPNHF allow him to advocate for a national forest reserve.

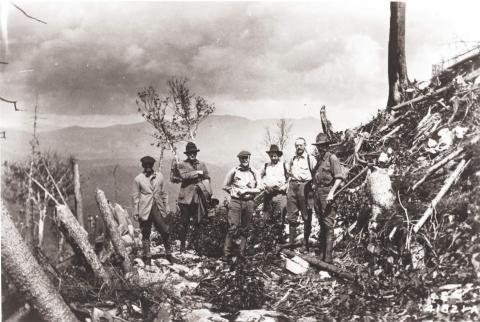

Ayres went on the lecture circuit, speaking to any group, from schools to chambers of commerce, that wanted to hear about the White Mountains. He “assembled a coalition made up of diverse elements—loggers and pulp manufacturers, nature lovers, hotel owners, political leaders, literary figures, and just about anyone else who could see the economic and environmental advantages to saving the White Mountains.” Ayres argued that the White Mountains “were a national treasure.”

There were six great lumber companies, each with a well-equipped logging railway, stripping the White Mountains with the most scientific efficiency that Yankee ingenuity could invent. [SPNHF] wanted to save at least a portion of it, and needed a forester. I suggested a National Forest in the White Mountains as the most direct and only adequate remedy.

—Philip W. Ayres

From 1901–1911, unfettered logging proceeded apace and fires followed. In 1903, 80,000 acres burned. In 1904, 200,000 acres burned. In 1907, 35,000 acres burned. Each year, smaller fires burned additional acreage. During the same time, the movement to create eastern national forests spread nationwide.

On January 10, 1903, the New Hampshire legislature approved the creation of a federal White Mountain reserve “by purchase, gift, or condemnation according to law.” It also approved the expenditure of $5,000 to survey the White Mountains for such a purpose. In national publications, Ayres recognized that the movement was “an attempt to preserve what remain[ed] of the forest cover” and reiterated that the state alone could not do that. “State ownership … cannot be brought about except gradually and meantime the virgin forests are rapidly disappearing.”

Ayres addressed Congress for the first time in 1902. He gained the support of various national groups: from the American Pulp and Paper Association to the American Forestry Association. He wrote articles in the Concord, Manchester, Boston, and

New York newspapers, urging readers to contact their congressmen to protect both the scenic and business elements of the White Mountains. Largely at Ayres’s urging, Senator Jacob H. Gallinger and Representative Frank D. Currier, both of New Hampshire, introduced the first White Mountain forest “reservation” bill into Congress in December 1903. Over the next several years, it moved slowly through various committees and hearings.

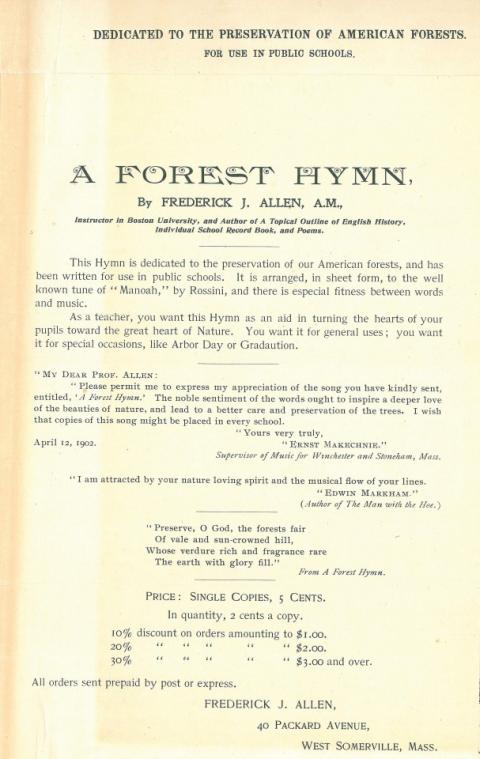

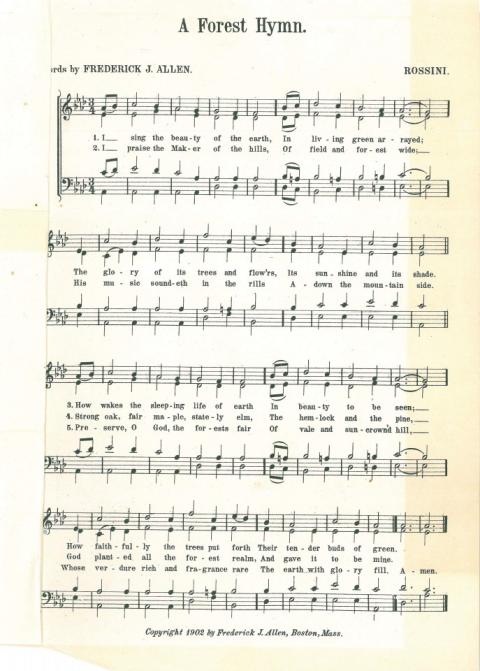

“A Forest Hymn”

by Frederick J. Allen.

The Hymn is dedicated to the preservation of our American forests,

and has been written for use in public schools…As a teacher, you want this Hymn as an aid in turning the hearts of your pupils toward the great heart of Nature.”

“Preserve, O God, the forests fair

Of vale and sun-crowned hill,

Whose verdure rich

and fragrance rare

The earth with glory fill.

Southern forest advocates, led by Gifford Pinchot, wanted to preserve a large stretch of the southern Appalachians. At first, Pinchot resisted working with New Englanders. In January 1905, Ayres and Pinchot met at the first American Forest Congress. “Dr. [Edward Everett] Hale got out of a sick bed in order to speak for the White Mountains [where he had ‘helped to make the original surveys in the White Mountains when he was a youth under twenty … fully sixty years earlier …’] With his eloquent voice, he told the story of the White Mountains, and offered a resolution that was received with great enthusiasm and referred to the Committee on Resolutions.” Dr. Rothrock, known as “the father of forestry in Pennsylvania,” said to Pinchot, “Now, Gifford, your bill for a National Forest in the Southern Mountains has been tried out in Congress and failed. It always will fail until you get those Yankees behind it. You have got to have these New England votes and you might just as well agree to a National Forest in the White Mountains.” Pinchot did agree. The Forestry Congress:

approves and reaffirms the resolutions of various scientific and commercial bodies during the past few years in favor of the establishment of national forest reserves in the Southern Appalachian Mountains, and in the White Mountains of New Hampshire, and that we earnestly urge the immediate passage of bills for these purposes.

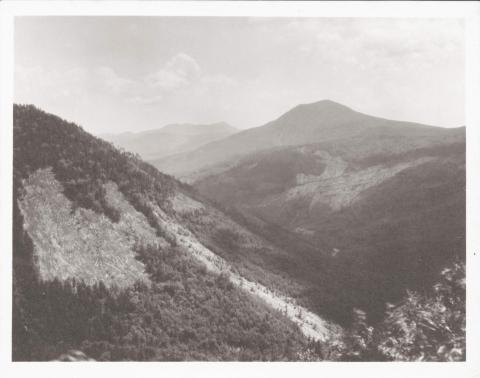

Despite the talk, conditions did not change in the White Mountains. In the October 1907 edition of Forestry and Irrigation, editor Thomas Will wrote: “Again prophecy has become history. On August 10th [1907] Forester Ayres of the Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests and Secretary Will of the American Forestry Association sat on Mt.Lafayette and looked over some 25,000 acres clean cut by the J.E. Henry Co. The ground was thickly covered with branches, tops and logs. They predicted that forest fires would soon sweep this region. On Aug. 27th, seventeen days later, the Boston Post said in part in an editorial: ‘In the once virgin and beautiful White Mountain region it is happening as predicted. Following the lumberman comes the fire, and it is the end of forest beauty for not less than a generation and perhaps forever. … Survey from Mt. Lafayette shows Mt. Bond to be swept clean, the easterly slope of Mt. Garfield burned over, and the southerly slope of Mt. Guyot fiercely burning with flames eating up Mt. Lafayette.’”

Fire burned for many days during the second half of August. Thomas Will reported in September 1907 that:

It has become almost literally true that, where until recently stood a primeval forest, after cutting there remains standing scarcely a pole on which a bird can build its nest.

In President Roosevelt’s 1907 annual message, he declared: “We should acquire in the Appalachian and White Mountain regions all the forest lands that it is possible to acquire for the use of the Nation. These lands, because they form a National asset, are as emphatically national as the rivers which they feed, and which flow through so many States before they reach the ocean.”

Yet the bill stalled in Congress. One more person was needed: John W. Weeks. Philip Ayres, along with the President of the Appalachian Mountain Club and the Secretary of the Massachusetts Forestry Association, met with the representatives from all of the New England states in Boston on Halloween in 1906. Weeks was then a freshman Congressman representing the 12th District of Massachusetts. More importantly, Weeks was a native of Lancaster in northern New Hampshire. He had an intimate knowledge of the White Mountains having grown up there, and he continued to spend summers in Lancaster. Weeks promised to promote the idea in Congress. In 1908, Congressman Weeks rewrote the national forest bill, combining forest preservation with watershed protection and fire control. He “organized a successful campaign in the House” where the bill had been repeatedly defeated.

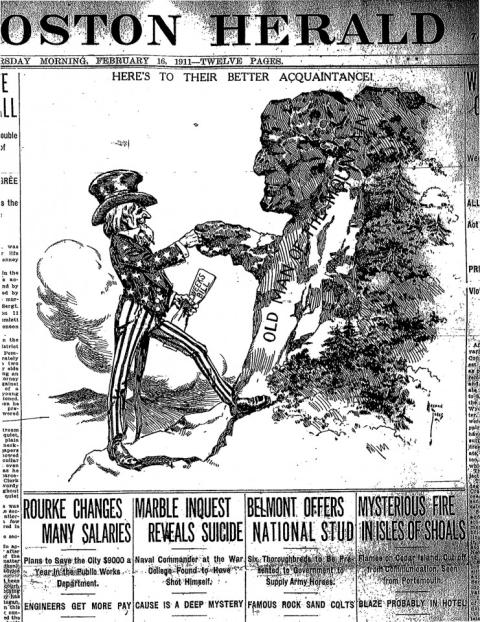

In January 1911, the SPNHF issued “An Appeal” for public assistance to pass the “White Mountain Forest Bill” to insure final passage. “The Weeks Bill for national forests in the White Mountains and Southern Appalachians is not making the progress in Congress that is necessary if it is to pass at this session of Congress, or before the White Mountains are denuded far more severely than they now are. The Senate has passed this measure three times in different forms, but is now waiting for action by the House. The House that passed this bill a year ago, in the previous Congress, is now engrossed in other matters. Where are the New England Congressmen?” The public responded with a deluge of letters urging more aggressive action on the part of New England representatives. The House and Senate versions were reconciled shortly thereafter.

The Weeks Act became law when it was signed by President Taft on March 1, 1911

When we speak of nature in this manner…

we mean the integrity of impression

made by manifold natural objects.

It is this which distinguishes the

stick of timber of the wood-cutter,

from the tree of the poet.

— Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Nature”

Protecting the Forest: The Weeks Act of 1911 Exhibition Tour

- Plymouth State University, Silver Center, March 3 – April 11, 2010

- The Balsams Grand Resort, Dixville Notch, NH, May 24-28, 2010

- Mountain Grand View Resort and Spa, Whitefield, NH, June 1-2, 2010

- Weeks State Park, Lancaster, NH, June 23 – September 6, 2010

- The Highland Center, Crawford Notch, September 2010 – January 3, 2011

- St. Kieran Art Center, Berlin, NH, January 16 – March 27, 2011

- National Forest Service, Campton, NH, Campton, NH April-May, 2011

- Mt Washington Observatory Weather Discovery Center, North Conway, NH

Memorial Day – Labor Day, 2011 - Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests, Concord, NH, September –

February, 2012