March 25, 2014 – March 8, 2015

Museum of the White Mountains, Main Gallery

Curated by Sarah Garlick, independent science writer and educator

The Beyond Granite exhibition explores the geological underpinnings of three of the most popular forms of recreation in the White Mountains: climbing, hiking, and skiing/snowboarding. We investigate the fundamental Earth processes that have shaped these mountains we love, and we make the connections between the stories of our outdoor pursuits and the stories of the land itself.

“We go outside to become connected. We run, swim, and ride. We paddle, climb, hike, and ski. When we engage with our full selves in the mountains, when our bodies are active, our attention focused and present—and perhaps with a little luck—we break through the barriers that separate us from what is wild.”

But what is it we are connecting to? The textured surface of the handhold beneath our fingertips. The weight of the ledge beneath our boots. The pitch of the snow slope we roll onto as our skis pick up speed. These points of contact reach into the stories the mountains hold themselves: stories of how the schists, gneisses, and granites came to be; stories of mountain uplift and mountain erosion; stories of a glaciated past and of a future heading toward warming.

The fundamental Earth processes that have shaped these mountains we love have also shaped us, through our experiences and our adventures. This is our shared geology, a science embedded both in our landscapes and our spirits.

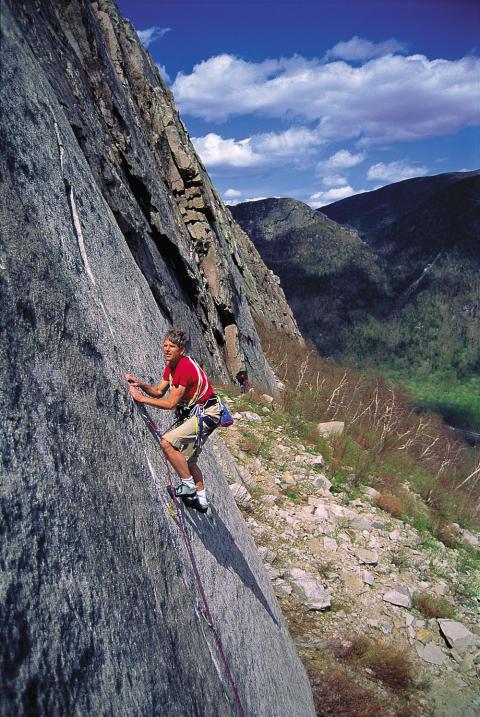

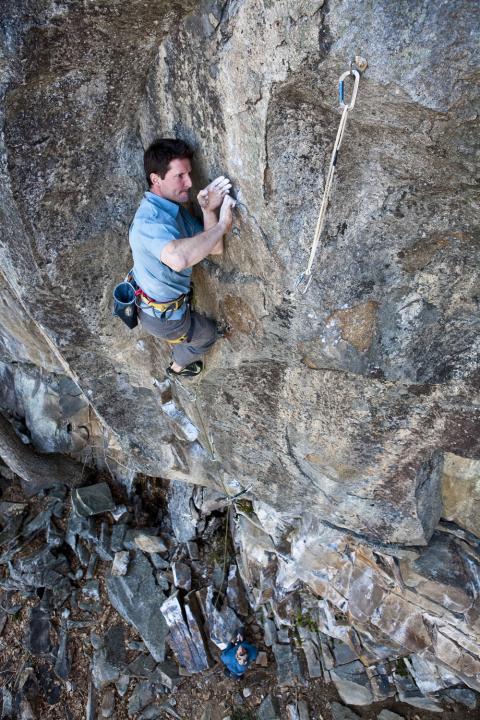

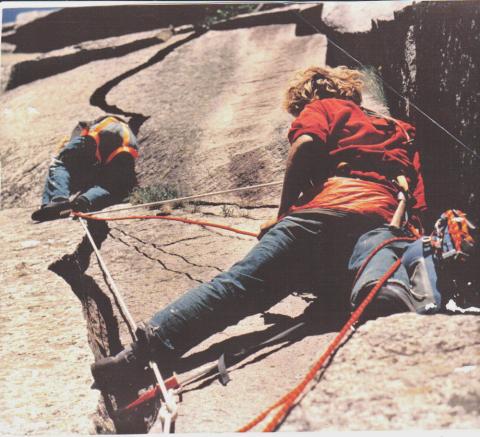

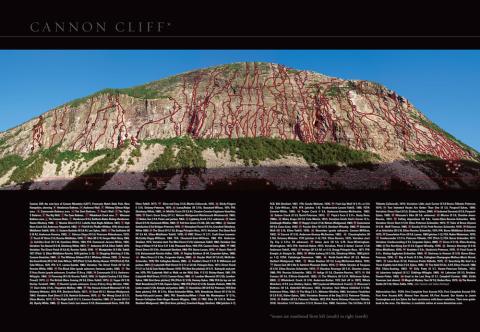

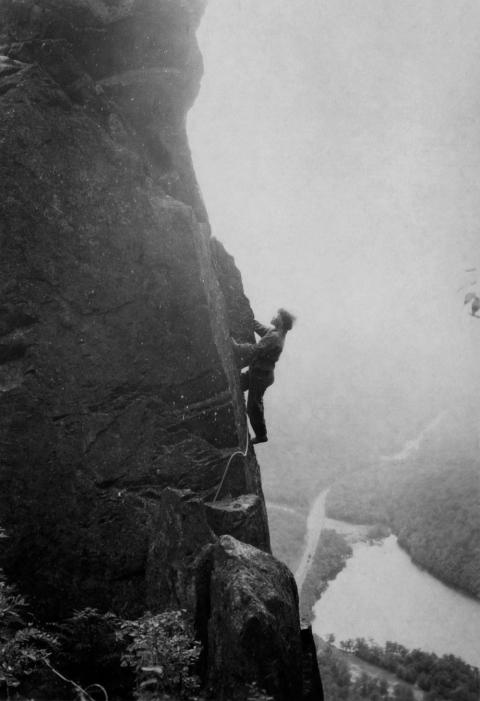

“Climbers crimp their fingertips onto tiny ridges of schist on overhanging cliffs. They paste their rubber climbing shoes against textured slabs of granite. Geology is the primary control of the rock climbing experience. In the White Mountains, different rock types lead to different styles of climbing.”

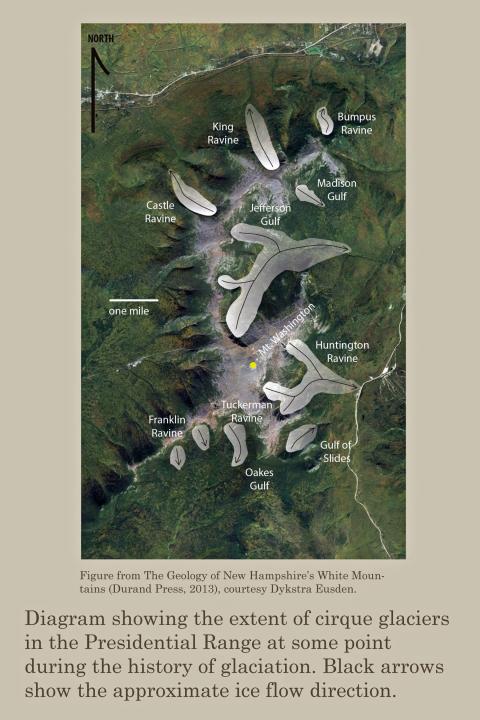

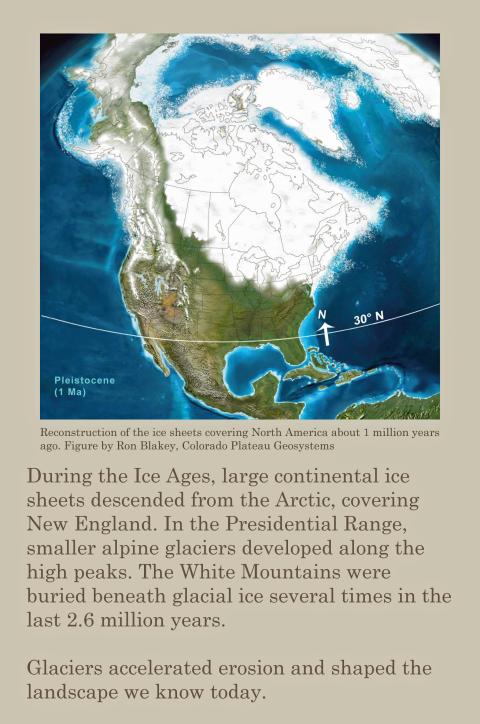

“Climate and landscape are deeply connected. The mountains have been sculpted by glaciers, landslides, rivers, and frost: forces that are dictated by climate. The Earth experienced multiple periods of cold climate between 2.6 million years ago and 11,700 years ago, a time known as the Ice Age. Ice Age glaciers shaped many of the iconic features of the White Mountains, including Tuckerman and Huntington ravines.”

GigaPan photograph by Jim Surette

“Some of the world’s best alpinists learn their craft and train in the White Mountains. The White Mountains may not be very high, but their steep terrain, combined with northern latitudes and a convergence of different weather patterns, produce conditions here that are comparable to those in the planet’s greatest ranges.”

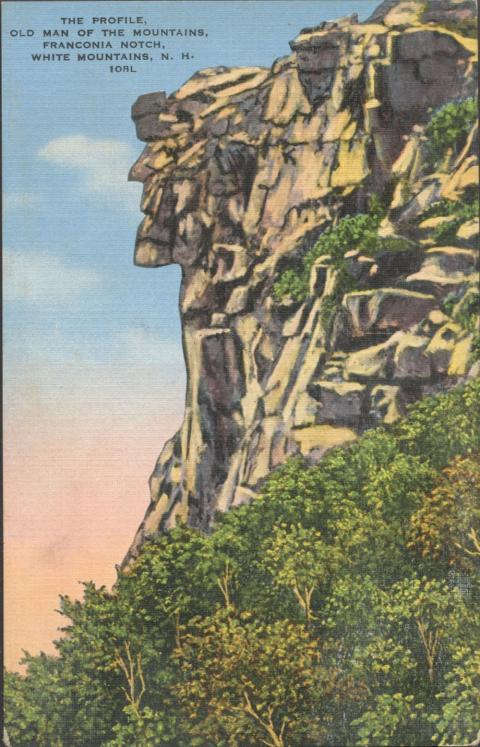

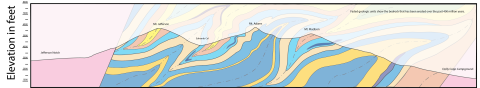

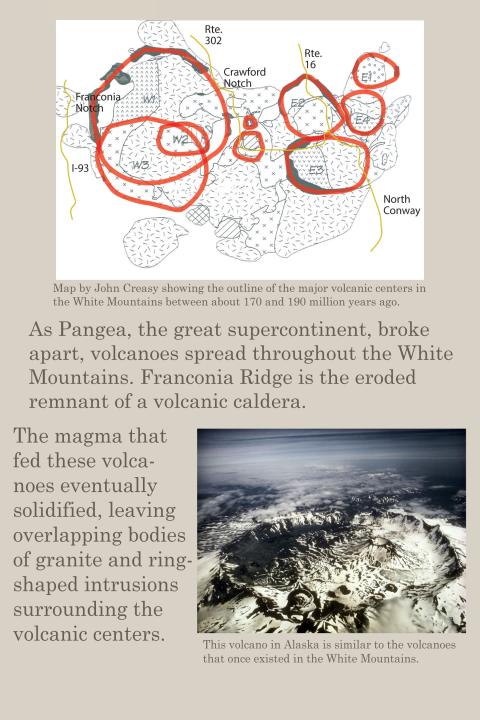

“The story of the White Mountains begins over 400 million years ago when a collision between continents thrust flat-lying rocks into high peaks in the Presidential Range. Other areas of the Whites, including Franconia Ridge, formed later when large volcanoes erupted across the region. At their maximum height, the White Mountains were about 15,000 feet tall—as high as the Rocky Mountains are today, but not as tall as the Himalaya.”

Gigapan photograph by Jim Surette

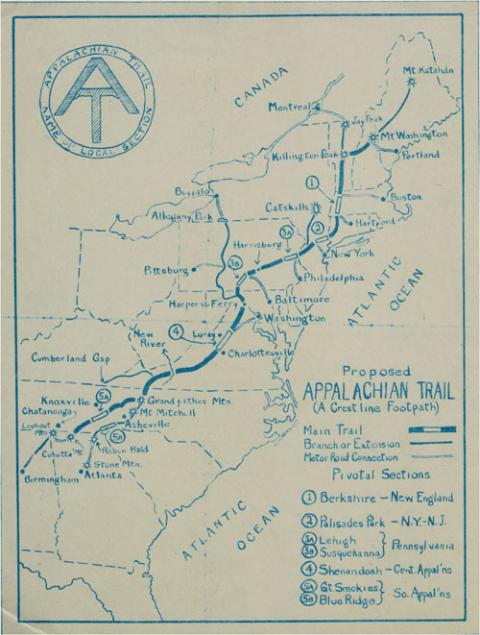

To hike the Appalachian Trail is to hike a seam where an ancient ocean once closed, bringing together all the world’s continents into a single landmass. When continents collide, it is analogous to a head-on collision of automobiles: rocks caught up in the wreckage are broken and crumpled into jagged mountains like the folded metal of a car’s front end. By the time Pangea was complete, the Appalachian Mountains stood as the planet’s grandest range, a belt of peaks stretching from Alabama to Newfoundland and even beyond, into mountains across Great Britain and Scandinavia.

The reconstruction of Pangea (below) uses modern political boundaries to view the supercontinent in the context of the world we know today. Strictly speaking, not all of these landmasses existed during the time of Pangea. The positions of many areas are estimated. Graphic by Massimo Pietrobon.

“The Limmer family has carried on the boot-making craft in New England for 90 years; it is a tradition that stems back to Europe.”

Peter Limmer completed his apprenticeship as a master craftsman in Bavaria in 1921. In 1924 he left his economically troubled homeland and worked in a Boston shoe factory until he started his own shoe repair business. Keeping his talents honed, he continued to make ski boots on the side after his arrival in 1924—a decade before skiing was a significant sport in the United States.

Skiing has long been a mode of winter transportation in the White Mountains, but the nature of skiing changed with the 1906 Nansen Ski Jump in Berlin, increasing local competitions, and, by 1928, the presence of two ski instructors at Pecket’s Inn at Sugar Hill. In the 10-year period that followed, skiing boomed into a popular sport with the opening of Black Mountain (1935), Cannon (1936), and Cranmore (1937). The political problems in Austria and Germany opened the floodgates to great skiing instructors migrating to America.

In 1939 Limmer was awarded the first patent for a ski boot in the United States. They could be used with wood skies from Ashland, New Hampshire and “European bindings” made in America. Now known as carefully crafted hiking boots, Limmer boots are also rich in mountaineering history. Members of the British- American Himalayan Expedition to Nanda Devi in 1936 used hob-nailed Limmer boots. In 2014 visitors can go to the barn in Intervale where the Limmer family moved in the 1950s, see the 1920s machines that are still in use, and be fitted for a pair of custom boots by Peter Limmer Jr.

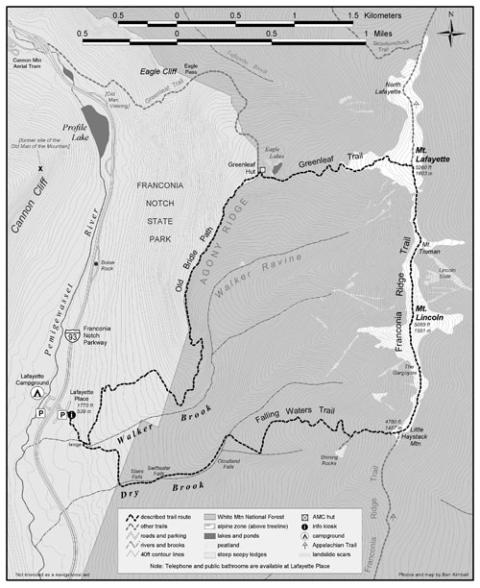

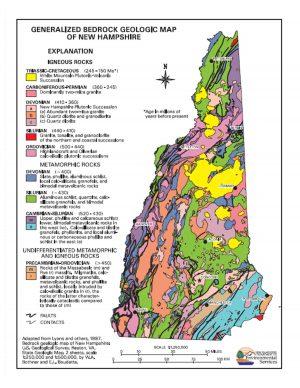

“Geologic maps show the pattern of different types of rock in an area—what you would see if there were no vegetation cover or soils, if the bedrock were 100 percent exposed.”

Each color on the map represents a distinct geologic formation. Geologists make these maps by hiking through the mountains and valleys, well beyond the trails, recording observations where rocks are exposed, and making inferences where ground is covered. Over time, as scientific theories advance and new terrain is explored, the maps change as well.

The influence of climate continues to play a pivotal role in our experience of outdoor recreation in the White Mountains, particularly in winter when most activities depend on particular snow and ice conditions.

The region’s climate is influenced by a complex set of geographic factors, including latitude, mountainous topography, and proximity to both oceanic and continental weather patterns. These, in turn, are affected by trends in global climate. The result is often dramatic variability in winter conditions, experienced both within single seasons and from year to year.

Scientists working in the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest, a Forest Service research site near the town of Thornton, have been measuring climate indicators like temperature, snowfall, and ice-out dates in the White Mountains for over 50 years. What they’ve found is that despite this variability that many of us have become accustomed to, two longer term trends are still clear: winters in the White Mountains are getting warmer and they are producing less snow.

What does the future hold for adventure in the White Mountains?

The effects of climate change have already influenced the ski industry, with a transition from small ski areas widespread across New England to large resorts concentrated in the northern mountains. These resorts now rely on substantial artificial snow-making operations to stay in business. Similarly, members of other winter recreation communities—backcountry skiers, snowmobilers, winter hikers, mountaineers, and climbing guides—have also noted the impact of changing winter conditions on their activities. Some of these changes involve characteristics that are central to not only recreation, but also to businesses and culture in the White Mountains.

From a geologic perspective, the ties linking climate, landscape, and human beings are tightly bound. We tap into these connections when we go into the mountains, through our experiences and observations. The mountains hold a deep time, but it is a narrative in which we also participate: the passing of minutes as our heart races during a hike or climb, the passage of generations as our sports and communities evolve, the advance of eons as the ground is altered and shaped.