Wayfinding: Maps of the White Mountains features maps from the far and recent past, as well as map tools for today’s hikers, tourists, scientists, weekend explorers, and enthusiasts. As the story of White Mountain maps progresses, we see the tremendous variety of maps, not just by type of map, but also by the range of aesthetic choices by the mapmakers, even for a given type of map, and even during relatively short periods of time. Each map describes specific places and routes, and also tells a story of the knowledge, curiosity, purposes, pleasures, and design ideas of its time. This gives the White Mountains one of the richest cartographic histories of any single mountain region in the world.

The Museum of the White Mountains is located on N’dakinna, which is the traditional ancestral homeland of the Abenaki, Pennacook and Wabanaki Peoples past and present. We acknowledge and honor with gratitude the land and waterways and thank the alnobak and Abenaki elders who have stewarded N’dakinna throughout the generations.

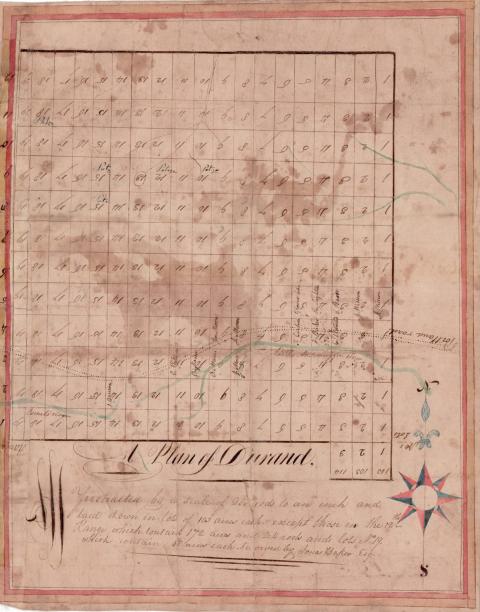

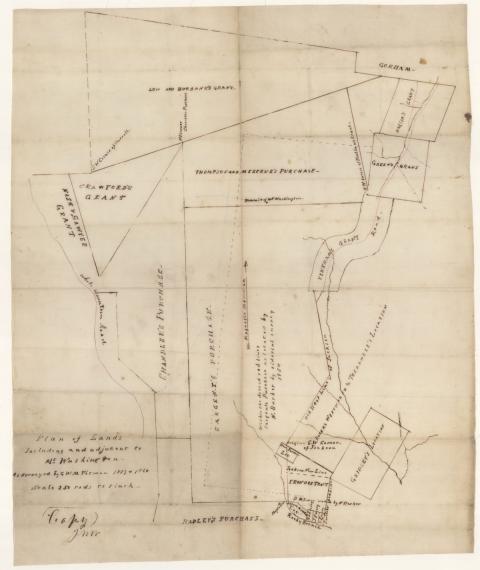

By the second half of the eighteenth century, the cartography of the White Mountains area was weak since “the region held little of commercial or political interest until the development of tourism, in the second quarter of the nineteenth century, and then of the logging industry, late in the century.” What maps there were of the region, were primarily the work of local surveyors and mapmakers.

Indeed, throughout the first three-quarters of the nineteenth century, maps of New Hampshire and especially of the White Mountains were largely the work of local cartographers….

It wasn’t until the end of the century, with the arrival of the U.S. Geological Survey, that the mapping of the White Mountains again became the province of professional cartographers with national and international experience. Even afterward, most maps of the region were produced by non-professionals, though some worked to very high standards indeed.

Adam Apt, “The Cartography of the White Mountains,” WhiteMountainHistory.org/White-Mountain-Maps

Transcript of the letter sent to Leavitt by his Boston publisher

Boston Feb 14, 1855

Dear Sir,

Your favor of the 13th was duly rec’d. Your drawing is in good order and ready for printing. I should be please to receive an order from you for printing your plate. They cannot be printed for a less price than the first order. I will print them on thin paper for ($10) ten dollars per Hundred – on thick paper for twelve dollars per Hundred Copes. Cash.. You will please remember that you gave me some trouble last year in paying for the map, pleading poverty. Now you tell me that you have sold all the maps. I do not think I shall allow you to do the same again. I will print the map, any number you shall order, but I must have the money on delivery. I wish you to understand I want you to come up to the mark & you shall have your work done in first rate style. Now friend Leavitt, I know you mean to do right & so do I. You have my best wishes for your prosperity.

Sincerely yours,

John H. Bufford

260 Washington St

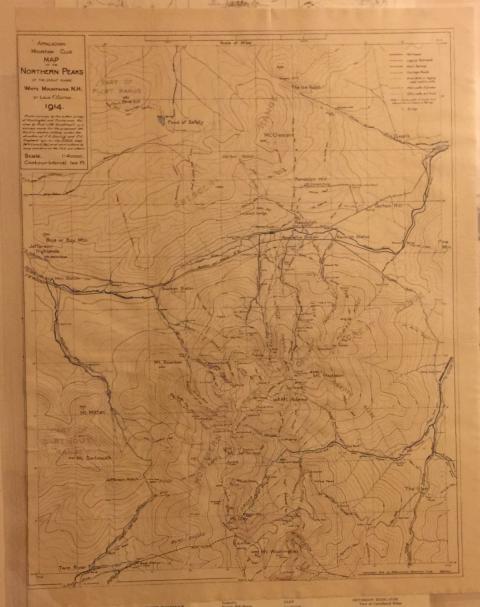

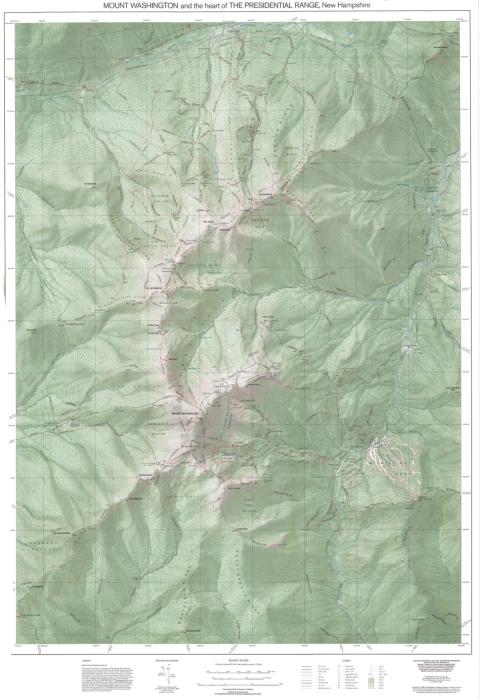

Cutter’s first map published by the Appalachian Mountain Club appeared in 1898 as a blueprint, and was of the northern Presidentials. In 1916, this map was expanded south over the whole of the Presidential Range and adjusted to the scale of 1/62, 500, and it then continued in that same form, with Cutter’s name still on it, up to 1992, after which the AMC adopted GPS technology and produced wholly new maps. For generations of hikers, Cutter’s maps were pretty much the only maps of the White Mountains that they ever consulted.

Today’s Mapmakers

As a middle school science teacher and avid hiker, I enjoyed taking my students on a hiking field trip every year. To prepare for the trip we practiced map reading, learned about topographic maps, and did some orienteering. The culminating project was creating a 3-D topographic map. It was fun and creative.

I made a model of Mt. Washington with some of students. Most students knew Mt. Washington was the tallest but soon learned that some of their classmates had climbed it, taken the Cog Railway or traveled up the Mt. Washington Auto Road. The 3-D model was a great prop for students to visualize the mountain and share their enthusiasm and experiences. Students enjoyed tracing their routes with their finger as they told their stories.

I thought: what if I created models of all 48 of NH’s 4000 mountains? Hiking friends could compare routes and stories, could revisit memories of past hikes or plan their next hikes. Hikers love to share their 4000 foot experiences and their enthusiasm might entice others to get started on their own 4000 foot list.

Mark Thomas

Past cartography tools include compasses, mylar sheeting, planimeters, and dividers – all of which are used to create analog maps. As digital mapping has become more popular, modern cartography tools have changed significantly.

Theodolite. Courtesy of Squam Lakes Natural Science Center with assistance from Thomas Stepp

A theodolite is a surveying instrument with a fully pivoting telescope which allows it to measure both horizontal and vertical angles. This Kern DKM3 is accurate to within 1/10th of a second of arc. What this means in actual surveying is that over a distance of ten miles the horizontal error would be only 1/3rd of an inch.

For the Squam Lake/Squam Range survey work, the theodolite would have been used both for critical horizontal and vertical angles to important survey stations, and for many of the several thousand other measurements used to establish the shoreline, the depth sounding grid points, and many other details on both maps.

Geodimeter. Courtesy of Squam Lakes Natural Science Center with assistance from Thomas Stepp

For Brad Washburn’s 1968 edition of his Chart of Squam Lake and map of the Squam Range (1973) the Geodimeter was used, along with a theodolite, for establishing an extremely accurate grid of survey “control points.” These were metal discs cemented into rock on, for example, the summits of Mt. Morgan, Rattlesnake Mt., and Red Hill.

“Geodimeter” is an acronym for “Geodetic Distance Meter.”

LIDAR Technology

Crawford Notch. Courtesy of The New Hampshire Geological Survey (NHGS)

LiDAR stands for Light Detection and Ranging. A LiDAR unit sends out laser light pulses which bounce off of any surface they hit and are reflected back to sensors in the LiDAR unit. The receiver then notes the time it took for the light to travel to the ground and back, and uses the total travel time to calculate the distance to that surface. As the unit moves along a set route, it sends out laser light pulses toward a target, typically the ground. Using Global Positioning System (GPS) information, these distance measurements are transformed into three-dimensional points (termed a “point cloud”), which can then be converted into accurate location and elevation information. This data can be extremely difficult to obtain otherwise.

LiDAR is also useful in visualizing landscapes that are covered by trees, as we have here in New Hampshire. Laser light pulses return to the LiDAR unit from different surfaces near the ground, including trees, buildings and the earth surface. In a tree-covered area each laser pulse may be reflected off of more than one surface, where part of the beam bounces off of the leaves, and another part of the beam travels further and reflects off of the ground. Later, a LiDAR “point cloud” undergoes processing to remove trees and buildings, revealing details of the ground surface that would not be visible on a regular photograph. The resulting product is called a bare-earth surface.

Franconia Notch. Courtesy of The New Hampshire Geological Survey (NHGS)

The Franconia Notch and Crawford Notch images are bare-earth hillshades. A hillshade is a 3D representation of the Earth’s surface which uses an imaginary light source to cast shadows on a landscape created by LiDAR. By default the light source “shines” from the northwest direction, and from an altitude in the sky of 45 degrees. Sometimes it is useful to change which direction the light is coming from, as this can make subtle features more apparent.

Mount Washington Hill Slope

The Mt. Washington Slope image uses a slope function instead of hillshade to show elevation information. The slope function calculates the difference in height between the pixels, or cells, in an image and then assigns a color value depending on how great the difference is. Usually the greater the elevation difference the darker the color, so a very steep slope is shown as dark gray while a flatter surface will be almost white.

The slope style is used when the information about the steepness of a hillside is important. For example, a person viewing the map would very quickly be able to tell where all of the steep slopes are simply by looking at the darker areas.

Mount Washington Hill Shade

Hillshade is often used when depicting a more natural view that is easy for the viewer to understand, because it represents what a person would see if looking down on the landscape with the Sun shining at an angle on the land.

It is interesting to compare the hillshade and slope function display styles in the same area. If you look at the Mt. Washington Shade image and the Mt. Washington Slope image you can see that even though they show the same region, they look different. The type of display style that is used for a given map depends on the traits that the person creating the map wants to highlight.

The New Hampshire Geological Survey (NHGS), part of the New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services (NHDES), in collaboration with the United States Geological Survey (USGS), the White Mountain National Forest, and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), acquired LiDAR data for the entire state during the late 2000s and throughout the 2010s. In addition to providing a critical tool to support resource management, this information is a great way for the public to understand the land around them, from being able to see long-abandoned stone walls deep in the woods, to glacial deposits that can be several miles long.

The idea of seeing the Whites from the coast may be farfetched today, but the projected 40,000 Abenaki whose history was already happening utilized an economy that influenced the atmosphere much more gently. The indigenous relationship with the present-day White Mountains and Mt. Washington in particular was one of reverence – they purportedly did not venture deep into the mountains due to their sacred religious status (Prins, 1994).

While it is difficult to know with certainty whether the Abenaki explicitly mapped the White Mountains, historians are familiar with their cartographic practices more generally. It is safe to assume that a variety of cartographic representations of these mountains were created and that the unchanged lines that separate what we now call the Presidential Range from the sky have been drawn for much longer than our artifacts indicate.

Since maps are products of cultures, if those groups seek to expand their claim to territory, mapping must logically precede expansion. Cartography may be aptly identified as fundamental to the process of colonialism.

….The end outcome of these colonialist acts of representation was that what is “known” about indigenous peoples of the Americas is known only from a European point of view.

Adam Keul, Project Humanist

Left: Indian Trails by Chester B. Price: The Lakes Region of New Hampshire, 1956

Courtesy of David Govatski

Right: Wabanaki Country. Stacy Morin. Orrington, ME. 1989

Courtesy of David Govatski

Early Maps

The broad sweep of the history of White Mountain region’s mapping begins with the description of the first known European map, a hand-drawn sketch from 1642, whose purpose, we may presume, was to give an impression of the territories that the English settlers might hope at least to explore, if not occupy.

Adam Apt

John Foster. A Map of New-England.

1677. Shown here is the 1826 facsimile

This celebrated woodcut map is the first map printed in British North America, and is also the first to show the White Mountains by name, though not the first map to depict mountains in the region. The London printing includes the mistaken label “Wine Hills.” John Foster was the printer and is presumed to have been the map’s Boston engraver. Shown here is the facsimile included in the 1826 reprint of a different book.

Left: Map of New Hampshire. Daniel Sotzmann. Hamburg. 1796

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division

Right: A New Map of New Hampshire. Jeremy Belknap. Boston. 1791

Courtesy of Adam Apt

Many early state maps such as those by Sotzmann, Belknap, and Carrigain, relied mainly on local resources, and played a role in the effort to define the fledgling state in word and image.

Belknap's 'A Map of New Hampshire'

Jeremy Belknap published this map in the second of the three volumes of his History of New Hampshire. It identifies a number of mountains, included, for example, Royce and Kearsarge, and a number of rivers, including, for the first time, the Cutler River, which Belknap evidently named for the Reverend Manasseh Cutler (1742-1823), his companion on his 1784 expedition to Mount Washington.

Sotzmann's 'Map of New Hampshire'

This map is one of several state maps that Sotzmann engraved for a German atlas of North America that was never completed. His maps were based on earlier maps, and the New Hampshire map is based on ones by Holland and Jeremy Belknap (see elsewhere in this exhibition). This is the first map to indicate Mount Washington, here labeled “Washington B.” (for “Berg,” meaning “mountain”). The first reference to “Mount Washington” in print occurs in the third volume of Jeremy Belknap’s History (1792) where the wording of the reference suggests that the name was becoming common usage. The map shows, however roughly, the Presidential Range, oriented from northeast to southwest. None of the other ranges or peaks is depicted in a way that conveys much accurate information of size, extent, or orientation.

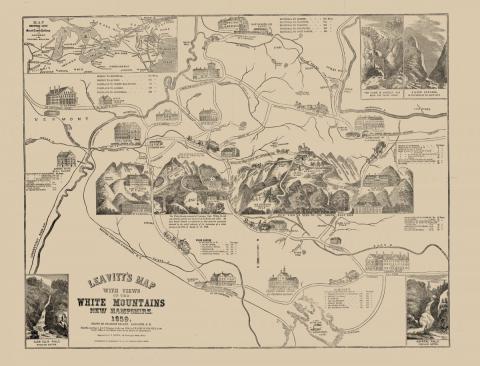

Franklin Leavitt’s first map of the White Mountains, published in 1852, was one of the first three published maps of the White Mountains. The others were Conant’s “Map of the Mountain and Lake Regions of New-Hampshire,” and the Tripp and Osgood “Map of the White and Franconia Mountains,” both of which were published the same year. It is notable that these first three maps were tourist maps, not topographical maps.

Three earliest White Mountain maps

Leavitt Map

Early in his life, Franklin Leavitt worked at the Notch House, an early inn near Crawford Notch. He also helped to build trails and the Carriage Road (now the Auto Road), and he worked as a guide. With the coming of the railroad to the White Mountains, he evidently concluded that there would be a market for a tourist map, and being unusually entrepreneurial, he drew one, and took it to one of the leading printing houses in Boston, Bufford’s Lithography, for reproduction.

David Tatham, an art historian who has written the authoritative articles on Leavitt, his maps, and his writings, observes, “As a rule, a mountain was shown if it was prominently visible from a hotel veranda, had a bridle path, was a notable landmark, or was the site of a memorable incident in local history.” He further suggests that someone, likely Bufford, the lithographer, improved Leavitt’s spelling on the first map, which is notably worse in Leavitt’s later maps. The scale used in the map is variable; distances are not consistently in proportion.

Leavitt continually issued new maps, which except in two instances were not really new editions of a previous map of his, but entirely new maps.

Tripp and Osgood Map

By 1850, there were 488 miles of railroad through New Hampshire, and the next year, the railroads began to bring tourists, in addition to explorers and adventurers, to the White Mountains. This map, published in 1852, was one of the first three maps of the White Mountains. (The others were Conant’s “Map of the Mountain and Lake Regions of New-Hampshire,” and Franklin Leavitt’s first map, both of which were published the same year.) Its crudity, in large part a reflection of its limited purpose, which was to encourage railroad travel to the region, was most decidedly not to be a topographical map. In this, it contrasts sharply with the Bond map, published one year later.

There were a couple of other versions of this map published in the next year or two, in different sizes, and with more hotels added.

Conant Map

Missing from this exhibition, but important to mention as part of the history of White Mountain maps, is an 1852 map made by Marshall Conant. The map shares with the first map issued by Franklin Leavitt, the distinction of being the first published maps of the White Mountains as a distinct region, having been issued in 1852.

The Conant map, however, is centered on the Lakes region, and so cuts off the northern part of the White Mountains.

It uses a cartographic convention of the time, not generally used later for the White Mountains, of representing mountain ranges as what today we call “caterpillars.”

Guyot's 1860 map

Guyot’s map, printed by one of the premier European cartographic publishers, was published twice: First by Petermann, and second, as an illustration for Guyot’s article “On the Appalachian Mountain System,” in American Journal of Science and Arts. The latter established the Appalachians (also, at the time, known as the Allegheny Mountains) as a single mountain chain. Guyot’s article reports in tables his extensive determinations of Appalachian summit elevations, but some values on this map are Bond’s, and are identifiable by their rounding to the nearest 100 feet.

Arnold Henri Guyot (1807-1884), a professor at Princeton, an associate of Louis Agassiz, and one of America’s most distinguished geologists and geographers, had emigrated from Switzerland in 1848 as a member of the vast wave of central European immigrants in the wake of the failed revolutions of that year, and in 1849 he first visited and began surveying the White Mountains, when he was living and lecturing in Cambridge. Guyot repeatedly visited the White Mountains in the course of his research. He used a highly sensitive hypsometer, a device that depends upon the measurement of the boiling point of water, rather than a barometer for determining altitudes. He and Bond were the only early cartographers of the White Mountains to have any familiarity with the Alps, or, for that matter, any mountains beyond the American east.

'Comparative view of the heights of the principal mountains in the world' map

The first graph of the relative heights of the world’s mountains appeared in 1786, but it and the ones that followed were more akin to bar charts than to artistic representations of mountains. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) felt that such graphs wanted improvement, and in 1813 he published his version, with the mountains of the western hemisphere thoughtfully juxtaposed against each other on the left, and those of the eastern hemisphere similarly arranged on the right. His design was the model for what became a very popular illustration through the nineteenth century, with countless versions appearing in atlases and printed on their own.

The example here, printed in Boston in 1820, is rare and perhaps only the second or third to follow Goethe’s design. In the key running down the left side, Mount Washington is no. 36, but because of an error, there are actually two mountains labeled “36” in the chart. This is the third (and fourth) appearance of Mount Washington on a map, because a chart of the comparative heights of the world’s mountains, on the pre-Goethe design, was published in London in 1817. Because this map was printed in Boston, it gives special attention to the mountains of the Northeast, and so includes the Blue Hills, barely noticeable at the bottom.

Note the tiny figure high up on the slope of Mount Chimborazo, on the left, then believed to be the highest peak in the western hemisphere. This represents Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859), who, in climbing that mountain to within 1000 feet of the summit in 1802 had reached what then was the highest elevation attained by a Westerner.

Note also on the right the elevation assigned to the summit of Dhaulagiri (meaning “White Mountain”), in the Himalayas, then the tallest known mountain in the world. The chart has text giving the precise source of this figure, which had been calculated by British surveyors a few years before, and is astonishingly close to the present value, though this is partly just luck, given that the definition of sea level has changed over the last 200 years.

Pickering's 'Map of the White Mountains'

William H. Pickering (1858-1938) was an astronomer and the younger brother of Edward C. Pickering, who founded the Appalachian Mountain Club (AMC) in 1876. He was active for many years in the AMC, serving variously as “Councillor for Improvements” and later president. He issued this map in 1882 in two publications: in the June 1882 issue of Appalachia, the quarterly journal of the AMC, and in a handbook entitled Walking Guide to the Mt. Washington Range. This handbook was the first guide written specifically for the hiker in the White Mountains, as distinct from the tourists, who might hire guides to lead them up the mountains. This map, correspondingly, may be considered the first hiking map of the White Mountains.

Note the contours, at the broad interval of 500 feet. Pickering wrote that “the observations on which this map is founded have been gradually accumulating since the summer of 1876, and are of four kinds: those made with the telescope, barometer, camera [lucida as well as photographic], and eye.” He uses a specialized nomenclature for mountains that had been devised by the AMC in one of its first meetings, in April 1876. In this system, the entire state of New Hampshire was divided into 26 regions with letter designations, and then major peaks were identified alphabetically within numbered areas inside each region, with subsidiary designations for subsidiary peaks. In this system, Mt. Washington is peak F6.1, being the highest peak in area 6 of New Hampshire region F. The horizontal scale is given in kilometers as well as miles. Early AMC publications sometimes used the metric system in addition to English measure, perhaps because so many founding members were scientists.

Cutter’s later AMC map of the Presidential Range, which has been continually issued since 1907, credited Pickering’s map as a source of information into its 1960 edition.

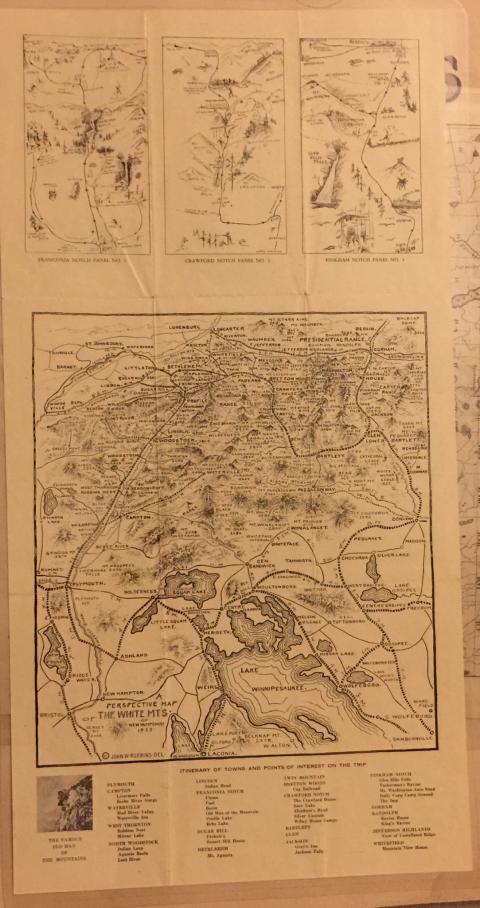

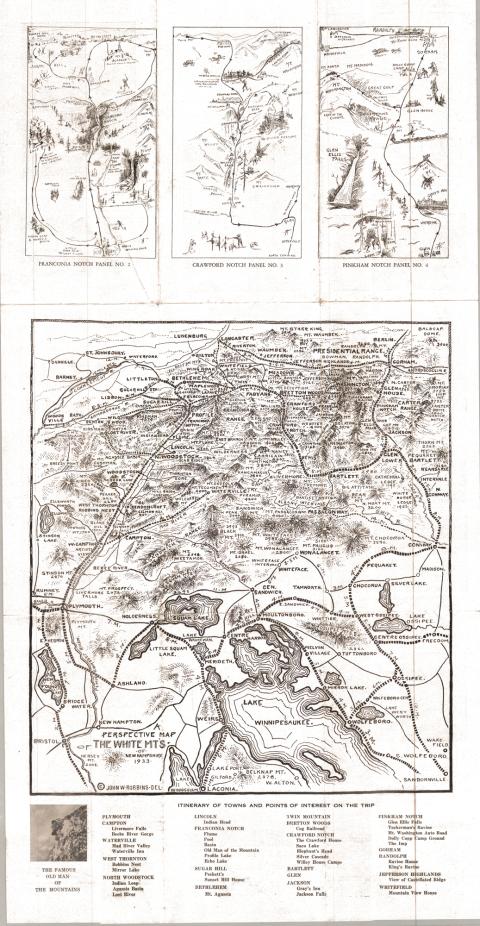

Maps of the White Mountains come in all shapes, sizes, technologies, and purposes. We can describe maps by fitting them into categories, but often the categories can overlap. This exhibition includes examples from several categories of maps including topographic, political, thematic, tourist and souvenir, street, bird’s eye, cadastral, panorama, and three-dimensional maps.

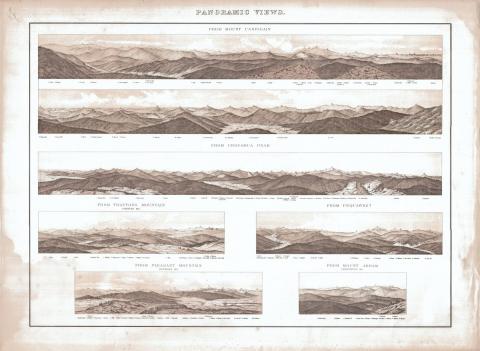

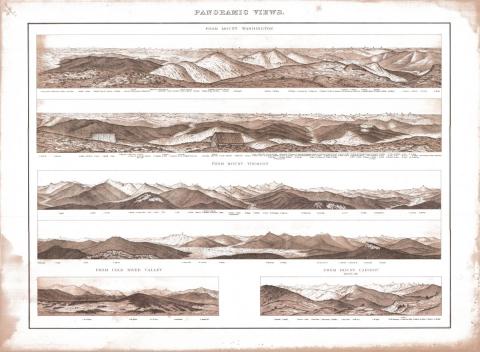

Panoramic Maps

Panoramic summit views were pioneered in the late 18th century. Panoramas of scenic places and events were very popular in the 19th century, usually displayed in large, round rooms where visitors could stand at the center of the scene. Summit panoramas in particular, on the printed page or on large paper sheets or foldouts, with their identification of the visible distant summits, were popular then and continue to be published to this day.

'The Most Perfect Map Ever Issued'

“The Most Perfect Map Ever Issued” is a ludicrous but charming representation of the White Mountain terrain. It also has a curious and obscure publishing history. In one form or another, it was printed many times, indicating that it was much loved. It is undated but presumably was published no later than 1880, because derivative versions bear that date. Some versions are much smaller, some have additional information, some less. It was used as late as 1904, when it formed the base for a map of an auto rally and gala.

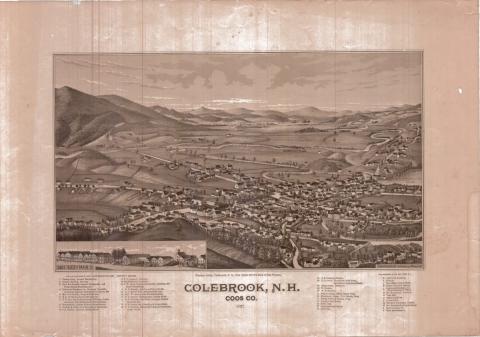

Bird's-Eye View Maps

Unlike most maps that represent abstractly the land as seen from straight above, bird’s-eye view maps instead create an idealized image of what the viewer might actually see if hovering in the air over the land, while still identifying natural and man-made features that a topographical map might show.

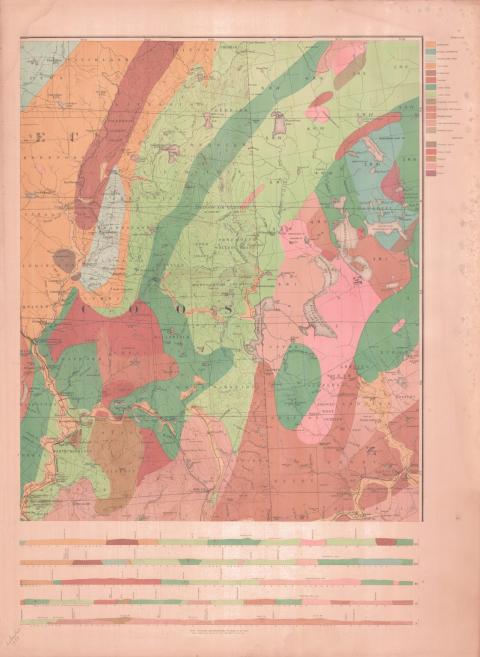

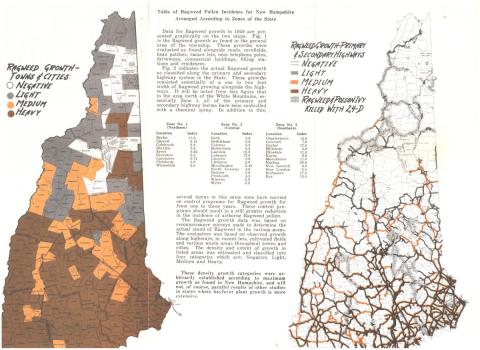

Thematic Maps

These maps illustrate a distinct subject of interest over a geographic region. Some examples in this exhibition are geological maps, a map of forests, a map of canoe routes, and a map showing areas where ragweed pollen is prevalent.

Political Maps

These maps have little to do with politics, as we normally use that word, but, rather, are maps that show the boundaries of political entities, like countries, states, counties, and towns. They may include topographic or other features, but only to show those features in relation to the boundaries. Maps of New Hampshire in this exhibition are political maps.

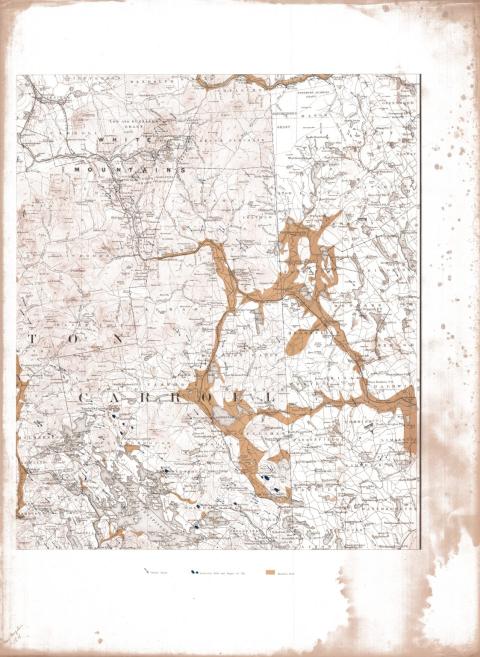

Topographic Maps

Topographic maps show the layout of the terrain, with features of the land’s surface, and where these are located, with respect to each other, and often with respect to latitude and longitude. Often, topographic maps will indicate elevations or altitudes, sometimes with contour lines, sometimes with another graphical representation, and sometimes just by assigning number, representing heights, to points on the map. Hiking maps are a kind of topographic map.

The first topographical map of the White Mountains

George P. Bond’s is the first topographical map of the White Mountains. Bond (1825-1865) was the son of William Cranch Bond, the first director of the Harvard College Observatory, at the time America’s premier astronomical observatory. George Bond, too, was employed at the observatory, and on his father’s death, became its second director. Bond’s first recorded visit to the White Mountains, in the company of other Harvard faculty members, was in 1849. He soon conceived a desire to map the region. He returned to the mountains many times, including a working vacation a few months before his early death, from tuberculosis.

He began his survey work in 1850. In 1851, he was sent by his father to Europe to establish relations with the major European observatories, though he took time out to see the Alps, and even on this trip, he was corresponding about instruments to borrow for completing his survey of the White Mountains. He returned to New Hampshire in 1852 to continue his survey.

This map is his only non-scientific publication. The map was accompanied by engravings of drawings by Benjamin Champney (1817-1907). It was reissued, unchanged, on India paper, in the first edition of Benjamin Willey’s Incidents in White Mountain History (1856), which is the version on display here.

All the summit elevations, rounded to the nearest 100 feet, are from Bond’s own measurements. Many White Mountain place names make their first appearance on a map here, though they may have been mentioned in texts. For example, this is the first appearance of “Tuckerman Ravine” on a map.

The names of Mounts Adams and Jefferson are the reverse of present usage and contradicted how many in Bond’s own time identified the peaks. Bond asked local folk the names of the various mountains, and he records Mr. Thompson, the proprietor of the Glen House, told him, “The prominent alpine peak north of Mt Washington was called Mt Jefferson + the smaller one next Mt W. was named Mt Adams. The reason he gave was that Adams was the next president in succession to Washington and that Jefferson was the tallest man.”

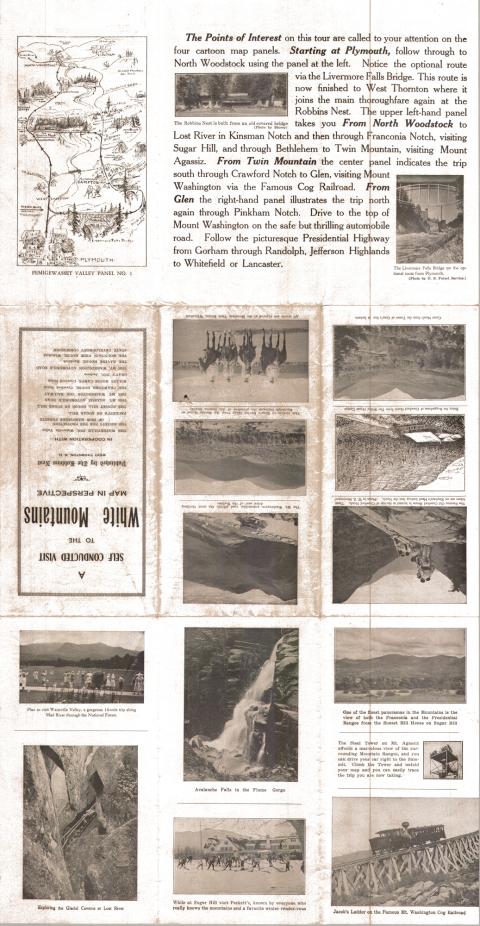

Tourist And Souvenir Maps

These maps give a sense of character of a place and flag the features of greatest appeal to the tourist. Although aesthetics are a consideration in the design of every map, for these maps, it’s the primary consideration. These maps can be mementoes from an experience or inspirations for a future visit. Sometimes, as with a topographic map printed on an envelope or postcard, the map is aesthetic design element.

Three Dimensional Maps

Schedler’s relief map is one of two raised relief maps published in the 19th century—the other is Snow’s, also on display in this exhibition—and is much the rarer of the two. It was published in 1879. It folds in half into its own box. It includes considerable detail. The cover notes that is was “compiled and prepared from the most recent information, surveys, and investigations, and embodying the latest corrections and revisions by members of The Appalachian Club.” This may be the only map of the White Mountains published in Jersey City. Schedler was well known as a publisher of globes; it was not known for its maps.

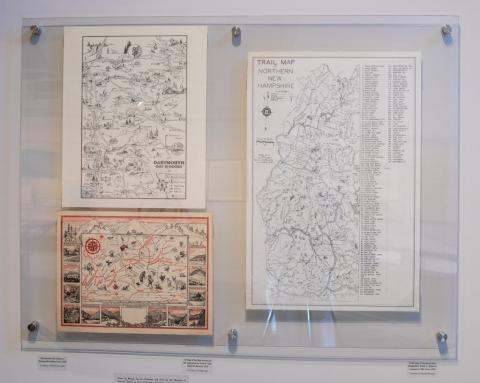

A selection of maps featured in the Wayfinding exhibition, courtesy of Adam Apt. Click to enlarge.

Resources

WhiteMountainHistory.org

- The Cartography of the White Mountains, by Adam Jared Apt

- 25 Early White Mountain Maps (high resolution scans)

- Scarce White Mountain Maps (high resolution scans)

- Franklin Leavitt Maps (high resolution scans)

- White Mountain National Forest Maps by David Govatski (high resolution scans)

- 1805 Town Survey Maps (high resolution scans)

Digitized Map Collections

- Harvard Map Collection

- Dartmouth College Digital Collections: Maps

- Osher Map Library

- US Geological Survey Topographical Maps

Kids Resources

New Hampshire Historical Society Moose on the Loose: Social Studies for Granite State Kids

Suggested Reading

Apt, Adam. Tolerable Accuracy: A History of White Mountain Hiking Maps. Pages 170-197 in White Mountain Guide: A Centennial Retrospective. Edited by Katherine Wroth. AMC Books. Boston. 2007.

Carchedi, David. Scaling the White Mountains. A Selection of White Mountain Maps. Jackson Historical Society. 2014. Jackson, NH.

Cobb, David A. New Hampshire Maps to 1900. An Annotated Checklist. NH Historical Society. Concord, NH. 1981. Pages 198-204

Cottrell, Bob. Toponomy and Topography. White Mountain History Blog. December 18, 2020. http://mwvhistory.blogspot.com/2020/

Garland, Larry. Entering the Digital Era. Pages 198-204 in White Mountain Guide: A Centennial Retrospective. Edited by Katherine Wroth. AMC Books. Boston. 2007.

Mudge, John. Mapping the White Mountains. Durand Press, Etna, NH. 1993.

Remembering Rodney Woodard. The Resuscitator. Spring 2011. OH Association. Newton, MA. https://www.ohcroo.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Spring2011.pdf