On View April 7, 2016 - October 7, 2016

Museum of the White Mountains

Curatorial Team: Marcia Schmidt Blaine and Cynthia Robinson

Ever since the White Mountains regions became part of the national consciousness, women as well as men have been drawn to them. What may surprise people is how often women have been leaders in the regions: from farm wives to climbers, from early hikers to modern businesswomen, from early conservationists to today’s environmentalists. The mountainous region gave women a place to explore their talents and creativity uninhibited by the constraints of urban life.

In the nineteenth century, female tourists opened up and popularized trails, explored the natural world, and wrote of the beauty, challenges, and discoveries they found in the mountains. In the twentieth century, women connected the White Mountain region to the larger world, while pushing the limits society imposed on them. Using art, letters, maps, clothing, and photographs, “Taking the Lead” will explore the role women played and continue to play in shaping and popularizing the region.

The first white women in the White Mountains viewed the mountains as granite barriers. While they may have recognized the beauty of the hills around them, they had to concentrate on the dangers inherent in living on the edge of the “civilized” world. Child births and deaths, wild animals, and neighbors too distant in times of need, plus hauling water and maintaining cooking fires in all seasons were just part of women’s lives. Their world was circumscribed, contained within and immediately outside their homes.

Life “was hardest on the women, hungering for someone to talk with, longing for the sight of another woman. The men could go hunting, and there was always the tavern where rum flowed like water. But a woman was kept home. She might lift her eyes to the mountains she saw from the small panes of her windows and wonder what lay beyond them. Blue and beautiful as they might be, outlined sharply against the sky, they were the unassailable wall. On the other side of them was the unknown; on her side, what had been and would always be.” Elizabeth Yates, The Road through Sandwich Notch

Like most pioneers, the women who came to the White Mountains to settle, left few traces. Their lives lived on in their journals, sketches, and stories told to descendants.

An 1840 journal entry by sixteen-year-old Mary Hale of Haverhill, New Hampshire shows her enjoyment of this approach to being in the mountains. “After supper we walked down through the [Crawford] Notch about two miles. The scene was truly grand immense rocks towering above our heads looked very frightful.”

But Hale also enjoyed climbing to the tops of mountains. She claimed to be the second “female” on top of Mount Lafayette. On August 25, 1840, “We started to go up Mount Lafayette at seven o’clock. It is three miles high, very steep, some places almost perpendicular…. We arrived at the top of the mountain at about eleven o’clock. The ascent is laborious but easily accomplished if done moderately. I arrived at the top of the mountain first. There never was but one female there before myself. Went above vegetation. The prospect was delightful.”

Lucy Crawford was a leader in many ways: a pioneer in difficult mountain living, an early innkeeper who tended some of the first true tourists in the White Mountains, one of the first women to climb Mount Washington, and an historian who recognized the uniqueness of her own time. Would she have recognized herself as a leader? Probably not.

The first white women to climb Mount Washington were three sisters: Eliza, Harriet, and Abigail Austin. Lucy Crawford wrote of the August 1821 climb, “They were ambitious and wanted to have the honor of being the first females who placed their feet on this high and now celebrated place.” The three intrepid women, accompanied by three men, travelled the long and difficult route following Ethan’s 1819 path to reach the mountaintop. It took them five days and three nights to complete the journey. Lucy her self, burdened by inn duties and childcare, had not yet climbed the mountain though she longed to make the trip. Additionally, her husband did not think the trip was suitable for women.

He relented four years later. Lucy Crawford recognized the importance of what they were doing in the White Mountains. Covering her work in her husband’s voice, she wrote a History of the White Mountains in 1846, recording not only the experiences of men in the mountains, but also those of women whose names might otherwise have been lost.

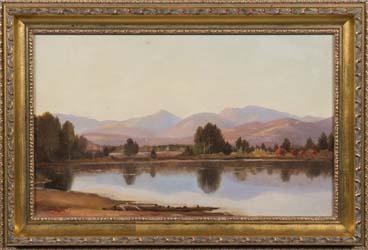

John William Casilear was drawn to the White Mountains. The reason he stayed was beyond the beauty of the environment; it included the beauty of the woman he met & married there. Casilear, born in 1811, was a bachelor of many years when he painting in the White Mountains with Kensett and Champney in the 1850s.

He met Helen Howard of Tamworth and, after a period of courting, they married in 1867. Researchers have found the location of the Howard Farm in survey records. There they had an exciting moment of confirmation when one lifted a fallen headstone to find Helen’s gravestone with “Wife of the Artist J.W. Casilear” on it.

Female artists were path breakers. Not only were they some of the first women to sell art or publish poetry, but their work helped to introduce an interested public, especially the middle class, to the wonders of the White Mountains. These women had to step outside the norm to be noticed. They walked a very fine line between acclamation and denunciation.

In 1859, poet and former Lowell mill operative Lucy Larcom joined Whittier and his friends in the White Mountains where she fell promptly fell in love – with the mountains. To a friend, she wrote, “To me there is rest and strength, and aspiration and exultation, among the mountains… I will go, and get a glimpse and breathe of their glory, once a year, always…. But I must not go on about the mountains, or I shall never stop.” Her romantic poetry focused on people’s understanding of and reaction to nature, generally using the White Mountains as her literary canvas.

So lovingly the clouds caress his head,—

The mountain-monarch; he, severe and hard,

With white face set like flint horizon-ward;

They weaving softest fleece of gold and red,

And gossamer of airiest silver thread,

To wrap his form, wind-beaten, thunder-scarred.

They linger tenderly, and fain would stay,

Since he, earth-rooted, may not float away.

He upward looks, but moves not; wears their hues;

Draws them unto himself; their beauty shares;

And sometimes his own semblance seems to lose,

His grandeur and their grace so interfuse;

And when his angels leave him unawares,

A sullen rock, his brow to heaven he bares.–Lucy Larcom, “Clouds on Whiteface,” 1868

Many women used flowers as their main inspiration, often ignoring the mountains behind them completely. Fidelia Bridges studied in Europe and established a respectable career painting primarily detailed botanical still lifes upon her return. Botany was immensely popular. Flowers and close-ups of nature sold. In many ways, her careful work highlights artwork done by women who never intended to exhibit their work.

Maria a’Becket’s artwork was widely known in her own time. Born Maria Graves Becket, she changed her name to a’Becket while studying painting in France. In 1884, she explained that she best liked to paint “old trees” that “bear the marks of long, hard struggles.” She was a path breaker. Art critic Sadakichi Hartmann recognized a’Becket as “a peculiar phenomenon in our art” with a “frail build” and “the vigorous touch of a man.”

A student of Benjamin Champney, Martha or Mary Safford’s art includes similarities of light and subject. MacIntyre notes “she signed her work with her initials or not at all, following a practice often used in the 19th Century to disguise women’s work, which did not sell as readily or at the same prices as men’s work.”

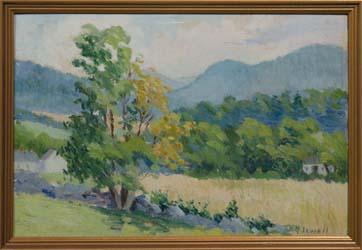

Elizabeth Jewell began her art career after her children were adults. She studied with professionals and went on painting trips throughout New England. Her work in the White Mountains was done in the early twentieth century.

“Emily Selinger (1848-1927) was an accomplished artist, author, poet, musician, writer of articles on art, monologues, and greeting cards…. From the mid-1880s until 1894 Emily and her husband Jean Paul Selinger (1850-1909) occupied a summer art studio at the Glen House, at the base of Mount Washington, in Pinkham Notch. Beginning in the 1894 summer tourist season they moved to the former art studio of Frank H. Shapleigh… at the famed Crawford House. Emily Selinger’s watercolor “Crawford Notch” and Jean Paul Selinger’s oil “Gateway of Crawford Notch, White Mountains, N. H. from Selinger’s Studio Grove” (Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College) are nearly identical. We can almost visualize them sitting next to each with easel and paints. The scene, painted dozens of times by a variety of artists, is across Saco Lake… toward Elephant’s Head, the Gate of the Notch, with Mount Webster in the distance. Today this view remains unchanged. We can literally stand where the Selingers stood and enjoy the view they depicted.” Charles and Gloria Vogel, “Jean Paul and Emily Selinger,” Historical New Hampshire 34, No.2 (Summer 1979).

It is worth noting that Emily Selinger was the only female artist-in-residence at any of the grand hotels in the White Mountains. In August 1888, the White Mountain Echo reported that “Mr. and Mrs. Jean Paul Selinger’s beautiful studio at the Glen House still continues to be one of the chief attractions of that elegant hotel. Mrs. Selinger receives every afternoon, surrounded by her own beautiful pictures of roses and chrysanthemums, and great jars and vases of the gorgeous wild flowers that are now in bloom.”

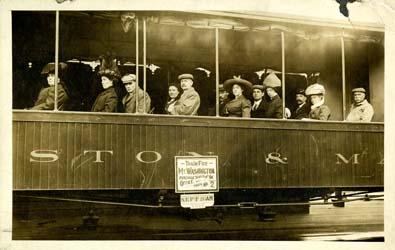

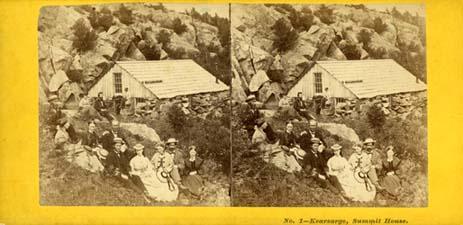

By 1855, Mount Washington was part of the experience female tourists could expect. Access to the trails was easier and it was possible to climb the mountain and return to the base in one day. Or, as many people did, hikers could stay the night at increasingly well-appointed Summit or Tip-Top Houses.

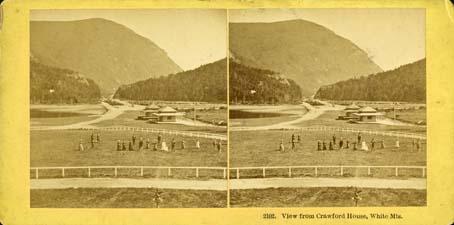

Stereoscopic views were immensely popular in the nineteenth century. The card with two pictures, taken a few inches apart, produces a three-dimensional picture when seen through a stereoviewer. They were found in many houses – allowing people to bring the outside and the White Mountains into their homes.

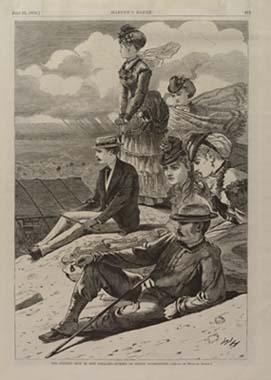

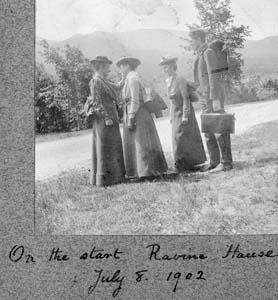

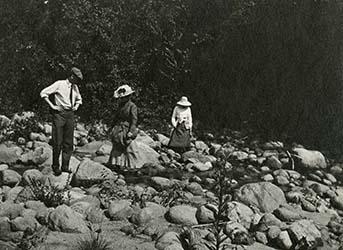

It is impossible to talk about nineteenth-century women hiking and climbing in the White Mountains without discussing clothing. Women’s every day garb was not suited to hiking, especially if bushwhacking. Not only did long dresses impede progress, but undergarments impeded breathing.

Photos may make female hikers of this period appear to depend on the help of men. With several pounds of clothing and the problems of even the shorter skirts while hiking, women could carry little else. On an 1882 White Mountain trip, each woman carried “‘her own satchel, attached to a leather belt, and a small canteen,’ but ‘all other luggage is delivered to the packman’,” who was hired specifically for that purpose. Note that male hikers also often depended on the same pack men to do the heavy work. Like their female hiking companions, they sought the physical challenge of hiking the peaks and not a test of strength in long-distance packing.

![Beginning of four day tramp over White Mts—Flash lights kitchen [of Halfway House] Two unidentified ladies working on snowshoes.](/mwm/sites/default/files/styles/max_width_480px/public/media/2025-01/camp-clothes-women7.jpg?itok=BlCXIj88)

Lucia Pychowska took on the question of dress in an 1887 article titled “Walking Dress for Ladies.” She urged women to wear low-heeled boots, woolen stockings, gray flannel, knee-length trousers secured with “loose” elastic, and two skirts, since “most ladies will find two skirts more agreeable than one.” “The under one may be made of gray flannel, finished with a hem, and reaching just below the knee. The outer skirt should be of winsey… or of Kentucky jean. Flannel tears too readily to be reliable as an outer skirt.”The outer skirt was longer, so “a strong clasp pin, easily carried, will in a moment fasten up the outer skirt, washwoman fashion” for going up steep slopes or moving through “hobble bush.” Thus outfitted, women could have “appeared at the end of these walks sufficiently presentable to enter a hotel or a railroad car without attracting uncomfortable attention.”

Our dress has done all the mischief. For years it has kept us away from the glory of the woods and the grandeur of the mountain heights. It is time we should reform.” Mrs. W.G. Nowell, Appalachia, 1877

Without changes in clothing, women would have remained on the sidelines of White Mountain history. Female hikers’ observations pointed out not only clothing issues, but the societal understanding that wives unquestioningly followed their husbands where they led.

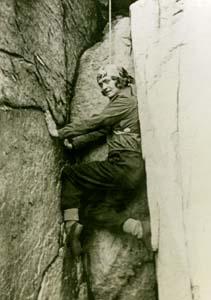

Increasingly, the challenges women found in the White Mountains were of their own making. They sought out difficult climbs, botanical knowledge, and trail building skills. But American society was still not ready to accept that outdoor life or physical challenges were appropriate for women in general. Instead, “certain” women were allowed to lead and to gain recognition and a bit of notoriety, not something most American women wanted. After all, what women cared to be known as one who would sleep in a space shared with strange men?

In 1873, Hoboken NJ residents Lucia Pychowska and her daughter Marian began spending summers in the White Mountains. It is impossible to know how many “firsts” these women made, but their importance lies more in their explorations of the mountains. Intrepid hikers, the original letters of Lucia, Marian, Lucia’s sister Edith, and their friend and fellow mountaineer, Isabella Stone carry the pride and excitement of their work in and love of the mountains.

Mary Perkins Osgood (later Cutter) was a summer resident of Randolph, a skilled botanist and artist who spent time studying and sketching wildflowers. Between 1895 and 1900, she produced five sketchbooks containing 244 watercolors of wildflowers. “Most of the plates include information in Osgood’s hand on the date and location of the flower’s depiction, as well as the flower’s systematic name; she rarely indicated the flower’s common name.” (Al Hudson, Randolph Mountain Club) Her work, which ended with her marriage and the births of her children, shows the many talents of the private artist/scientist.

I, happily and harmlessly following my beloved pursuit below the [cog railroad] platform, would hear such remarks as these: ‘What in the world is that old woman about? What’s she got in her hand?’ ‘Oh, it’s a butterfly-net! Did you ever?’ ‘She must be crazy. Just think of a butterfly up here. Why do her folks let her do it?’… I tell you I know from experience how it feels to be considered ‘a rare alpine aberration.’” Annie Trumbull Slosson, Bulletin of the Brooklyn Entomological Society

Multi-talented Miriam Underhill was a mountain and rock climber with few equals as well as a photographer of alpine flowers whose work was published.

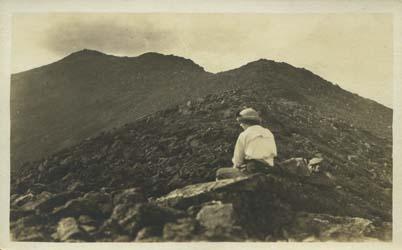

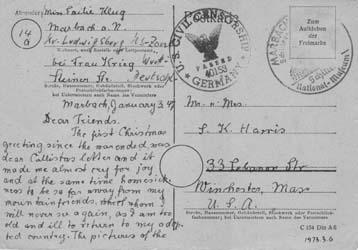

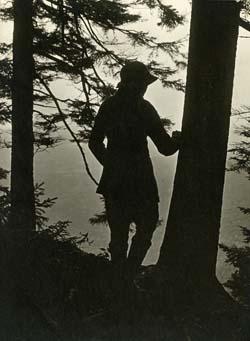

Emily Klug was a “picturesque tramper who became a White Mountain Legend.” She came to the United States from Germany early in her life. ” In the winter she was a nurse in a Brooklyn hospital. When summer came, she packed her camping equipment and left the city for the hills of New England.”

Emily Klug hiked alone. She spent three-four weeks each summer from 1912 until the mid-1930s in the White Mountains, carrying everything around her waist in a pinned-up skirt. She slept in the open and never complained of the weather. An AMC hutmaster wrote, “She carried her own sunshine with her.”

Women were leaders of the American progressive movement at the turn of the twentieth century. Activism was accepted as women’s work IF it could be seen as protecting their families. Americans recognized, even applauded, female activism that provided broad protection for families and communities, especially if it was done as part of an all-women’s group.

Alice E. Cosgrove of Concord worked for the New Hampshire State Planning and Development Commission to promote tourism. She created “Chippa Granite,” a boy who first appeared in posters advertising New Hampshire ski resorts in 1953. Her work also included a postage stamp with the Old Man of the Mountains, the design on the NH inspection sticker, and modern representations of New Hampshire tourism that often focused on the beauty of the mountains.

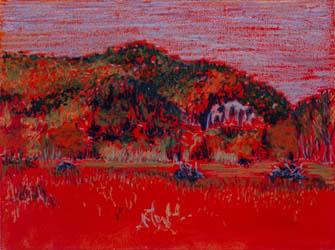

“Painting on location, I use gestural marks to explore the transience of the natural world. I choose colors and marks that best express random movement and the passage of time. In my paintings, classical structure sits on the edge of abstraction. Standing in the meadow, my vision took in the wide open space of the bare Cathedral Ledge. Vibrant hues surrounded the exposed rock, framing it with neighboring mountains. On October 17, the left panel was painted, while in the field that day, dogs barked and ran wild. The panel’s crimson color field, with associations of earth’s warming, served as the backdrop. There was enough time for my mark making to capture form and light, before a storm blew my painting to the ground. Returning October 19, the weather permitted the right panel to be painted. The presence of the meadow, rock formations and brilliant colors competed for my attention, as erupting beauty of daylight transformed to dusk.” Betty Brown, 2015

Betty Flournoy Brown, Cathedral Ledge Mt. Washington Valley Diptych. Oil on birch panels, 18 x 48 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

“Scientists say there may be as many as 12 percent of women that perceive millions of colors invisible to the rest of us. Studies have been done on “Super Vision” women who have a fourth cone as opposed to three. Results were found in a paper on color blindness on men in 1948 by Dutch scientist HL de Vries. I do not claim to have this super vision but it makes sense to me as a painter. I have always been asked, do you really see these colors? Sometimes I honestly do, but in a much less intense form. I take the values of color that I see and bump them up a few notches. I have learned from painting outdoors that the manufactured colors from the studio environment are very different from natures. Working outdoors is much more inspiring. Often I will apply an under painting on my paper, using the opposite color that I see. It gives me a jump start into the painting. I do know that I need to practice -paint a lot- to maintain my artistic vision.” Diane Taylor Moore, 2016

Intimate encounters with the wildness and “otherness” of nature is the core inspiration for my work. Exploring the interplay of culture and history in humankind’s relationship with nature and landscape are the motivation and inspiration for my paintings, along with my desire to protect, celebrate, and inspire others with the fragile beauty of the natural world.

-Mary Graham, 2016

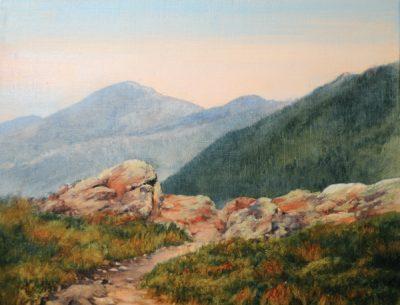

Lauren Sansaricq grew up in Columbia County, New York, where from an early age she was exposed to both the beauties of the Hudson Valley and, under the teaching of Thomas Locker, to the traditional painting techniques of the Hudson River School. Taking Mr. Locker’s advice Miss Sansaricq received academic training in drawing and painting at the Grand Central Academy of Art in NYC.Today Sansaricq’s work is in collections throughout the country, and is hung beside some of the best American painters of the past. She also teaches every summer on the Hudson River Fellowship, and now resides in the White Mountains.

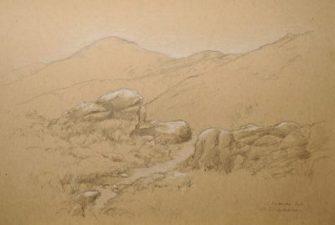

During her White Mountain National Forest Residency, Kyle Browne used natural materials to create site-specific ephemeral work that responded to the environment; drawing with graphite on paper to capture the shift of movement in time in the forest; and writing intuitive reflections and responses to her work.

In the mountains, the women who worked in the huts were already comfortable breaking traditional roles. They enjoyed the rugged challenges of the mountains and sought the work the huts presented. They wanted, or for some needed, to be deeply involved in the mountains.

Wake up, Huts Committee! We women are good for much more than making babies and keeping house for ‘hubby.’ We too love the mountains and what ruggedness they offer and the people that are tuned into them. It is possible to find some (many) of us who could maturely handle the co-ed situation and who know and respect ourselves well enough to save you any embarrassment…. Have confidence in us.” Cathy Ferree, 1971

In the fall of 1960, New York-based Laura Johnson Waterman joined the AMC’s beginner rock climbing weekend at the Shawangunks. There she met Guy Waterman and the two began climbing together, making extended trips up to the White Mountains. She took on very difficult rock climbs that no other woman, and very few men, attempted. The Watermans married and moved to Vermont in 1973, setting up an off-the-grid, self-sufficient life that gave them time for mountains. As environmental stewards, the Watermans began maintaining the Franconia Ridge Trail in 1980 under the AMC’s fledging Adopt-a-Trail Program. For the next decade and a half, they repaired cairns, cleared waterbars, cut brush, and kept the treadway clear of rubble while answering questions from hikers who asked them what they were doing. It was the perfect opener to further discussion about the fragility of the alpine terrain and the necessity for every hiker to become a steward. “The Franconia Ridge,” Laura said, “felt like an extension of our backyard; it felt like home.”

Marianne Leberman has been with the White Mountain National Forest for almost 21 years. She is currently the Recreation and Wilderness Program Leader for the Forest. She started by managing the campgrounds, all the developed sites in the summertime and working as a snow ranger in the winter.

So I fell in love with the mountains. Of course, I fell in love with them when I was skiing on them too. For me the mountains are my inspiration. When things aren’t going well/pretty crummy in my life I go out into the mountains. I go everyday anyway with the dogs, and we hike for an hour and a half—we go up a mountain around here. As often as I can then in the summer I drive up north and go into the Whites. I think I’ve celebrated every birthday since I was 15/16 on atop of a mountain in the White Mountains.” Penny Pitou, 2014

Today, women continue the efforts of early conservationists.The Forest Society, led by their President Jane Difley, is working to stop the hydropower transmission line towers from running through the mountain forests. In a 2013 piece written with Carolyn Benthien, chair of the Forest Society’s Board of Trustees, Difley states that “this proposal threatens our scenic landscapes and existing conserved lands, including the White Mountain National Forest, our own forest reservations, and dozens of other lands protected by other organizations. This is unacceptable.” Like earlier activist women, Difley understands that the value of the mountains is not simply monetary; the mountains provide much more.

The White Mountains have given women the opportunity to discover their own strengths. Women have hiked through scrub, hauled timber, contemplated great heights, painted the valleys, sketched the flowers, written of their mountain summers, camped on the ground, and discovered immense joy in accomplishment. Women have taken the lead, making a welcome path for others to follow – and to take up the lead themselves.

In preparation for the Taking the Lead exhibition students in 2014 history course, American Women’s History, interviewed women associated with the White Mountains. The women who were interviewed graciously granted students and exhibit-goers access to their memories and thoughts about their connections to the White Mountains. Students learned much from this project: ethics associated with interviewing, independent responsibility for their work, and deeper critical thinking skills, as well as indomitable role models for their future.

Highlighted Story

Rebecca Oreskes started working at the AMC’s base lodge in Pinkham Notch in 1979 and became manager for Lakes of the Clouds hut in 1983. Later, she turned to the Forest Service for her career and was surprised to find sex discrimination there. She was the only woman on a timber marking crew. “One day [we had]… bad weather…. our boss brought us all together and said ‘ok, we have tools that need to be worked on over at the equipment depot so all the guys can go there.’ And then he looked at me and said, ‘Rebecca, why don’t you go work with the girls in the office?’” The Forest Service adapted, and she remained and was promoted.

Rebecca Brown

Rebecca Brown founded the Ammonoosuc Conservation Trust, the North Country’s first locally-based, grassroots land conservancy and served as its first board president. Today, she is ACT’s Executive Director. Rebecca’s book, Women on High: Pioneers of Mountaineering was honored by the National Outdoor Book Awards.

Read Full Rebecca Brown Transcript (pdf)

No audio available

Jane Difley

Jane A. Difley is the fourth President/Forester to lead the Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests since it was founded in 1901. Jane was the first woman elected President of the Society of American Foresters, and serves on the Leadership Council of the Land Trust Alliance, the President’s Council of New Hampshire Audubon, and as a Director of the Merrimack County Savings Bank.

Read Full Jane Difley Transcript (pdf)

Click here to listen to the full audio

Margaret (Peggy) Dillon

Peggy Dillon worked at Pinkham Notch Camp and at AMC huts from 1979 to 1984. Peggy has almost 30 years’ combined experience as a newspaper reporter and photographer; magazine writer, editor and designer; speechwriter; historian; inner-city charter high school teacher; and college professor. She is currently a professor in the Department of Communications at Salem State College.

Click here to listen to the full audio

Jane English

Jane English is a physicist, photographer, journalist and translator. Jane received her B.A. in Physics from Mount Holyoke College in 1964 and Ph.D. from the University of Wisconsin-Madison for her work in high energy particle physics. She taught courses in Oriental thought and modern physics at Colorado College.

Read Full Jane English Transcript (pdf)

Click here to listen to the full audio

Judith Maddock Hudson

Judith Maddock Hudson is a longtime member and former president of the Randolph Mountain Club. Today, she serves as the Club’s historian. To celebrate the 100th anniversary of the RMC in 2010, she published Peaks and Paths: A Century of the Randolph Mountain Club.

Read Full Judith Maddock Hudson Transcript (pdf)

Click here to listen to the full audio

Marianne Leberman

Marianne Leberman serves as the Recreation and Wilderness Program Leader for the White Mountain National Forest, U.S. Forest Service. A skier who worked on ski patrols out west, her first work for the Forest Service includes serving as the first female Snow Ranger in for the WMNF.

Click here to listen to the full audio

Rebecca More

Rebecca Weeks Sherrill More, Ph.D., holds appointments as Visiting Scholar in the department of History at Brown University and Lecturer in History in the Division of Liberal Arts: HPSS, Rhode Island School of Design. Her lectures include colonial settlement in New Hampshire and the 1911 Weeks Act, which her great-grandfather Congressman John Wingate Weeks sponsored to further development of the Federal National Forest Reserves.

Read Full Rebecca More Transcript (pdf)

Click here to listen to the full audio

Jayne O’Connor

Jayne O’Connor is President of the White Mountain Attractions Association, marketing the State’s most active tourism region to domestic and international travelers. She has been awarded the Mildred Beach Travel Person of the Year Award, Travel Person of the Year, and the Governor’s Export Achievement Award for her work in international marketing. A New Hampshire and White Mountains native, O’Connor grew up at her family’s country inn in Franconia.

Read Full Jayne O’Connor Transcript (pdf)

Click here to listen to the full audio

Rebecca Oreskes

Rebecca Oreskes retired from the US Forest Service in 2013 after 25 years in various positions. Her last position was overseeing a wide range of programs, including recreation, wilderness, public affairs, conservation education and heritage as part of the White Mountain National Forest leadership team. Other assignments included working with International Programs in their Disaster Assistance Support Program and serving as Chair of the Chief’s Wilderness Advisory Group.

Read Full Rebecca Oreskes Transcript (pdf)

Click here to listen to the full audio

Alice Pearce

In 2015, Alice Pearce was named Executive Director of NH MADE. Prior to that, Alice served as executive director of NH Granite State Ambassadors and before that, for 21 years as president of Ski NH. In recognition of her efforts at Ski NH, Alice received Ski NH’s Whitney Award for outstanding contribution to the state’s ski industry and a commendation from the governor for service and commitment to one of New Hampshire’s most important industries.

Read Full Alice Pearce Transcript (pdf)

Click here to listen to the full audio

Penny Pitou

Penny’ Pitou is a former United States Olympic alpine skier, who in 1960 became the first American skier to win a medal in the Olympic downhill event. In 2001, Penny was inducted into the New England Women’s Sports Hall of Fame. Today, Penny owns a full service travel agency in Laconia, Penny Pitou Travel.

Read Full Penny Pitou Transcript (pdf)

Click here to listen to the full audio

Lindsey Rustad

Lindsey Rustad works as a Team Leader / Research Ecologist at the USDA Forest Service Northern Research Station in Durham, NH and associate research professor at the University of Maine. For more than 20 years, Lindsey has worked with a multidisciplinary team of researchers to assess the impacts of human-induced disturbances on forested ecosystems of northeastern North America, with particular emphasis on acidic deposition and climate change.

Click here to listen to the full audio

Mary Sloat

Mary Sloat has long-term and active connections to the White Mountains, having lived and worked in the mountains. Her first trip to the White Mountains was at age eleven to visit her uncle who managed the Crawford House. She currently serves on the Board of the Northern Forest Canoe Trail, the Citizen’s Advisory Committee for Nash Stream, the White Mountain Garden Club, and the Connecticut River Joint Commissions. Formerly vice-president of the board of directors of the North Country Council and chair of its Northern Forest Lands Committee, Sloat has taken leadership roles in the North Country League of Women Voters and 4-H.

Read Full Mary Sloat Transcript (pdf)

Click here to listen to the full audio

Barbara Wagner

In 1983 Barbara Wagner became the first female Appalachian Mountain Club hut manager and went on to become a Facilities Manager at the AMC. Today, Barbara serves as Senior Vice President and Chief Operating Officer at the Energy Foundation.

Read Full Barbara Wagner Transcript (pdf)

Click here to listen to the full audio

Laura Waterman

Laura Waterman is co-author of several books with her husband, Guy Waterman on the mountain history and environmental issues of the Northeast. In 1980, she and her husband undertook the trail maintenance and stewardship of the Franconia Ridge in New Hampshire’s White Mountains formed a close attachment to the Alpine areas of the Northeast.

Read Full Laura Waterman Transcript (pdf)

Click here to listen to the full audio