May 31, 2025 – September 13, 2025

Museum of the White Mountains, Main Gallery

Exhibition curated by Meghan C. Doherty

The Museum of the White Mountains at Plymouth State University was selected by New Hampshire Humanities as one of three host sites in the state for the Smithsonian’s Museum on Main Street exhibition, Crossroads: Change in Rural America. This exhibition explores pressing questions for rural communities: What does “rural America” mean? What makes these places unique? How do we identify with them? How have rural communities and small towns evolved and changed? Over the course of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, small towns became centers of commerce, trade, local politics, and culture. For some, the crossroads affirmed a new life in a new place. For others, the crossroads meant hard work and hard times. Crossroads aims to allow small towns and rural areas a chance to observe their own paths and to highlight the changes that have affected their trajectories over the past century.

To make this national exhibition more relevant to our local community, we are developing a companion exhibition, The White Mountains: A Crossroads, that explores the same themes of land, community, identity, persistence, and managing change in the context of the western White Mountains. We are doing this in partnership with the historical societies and public libraries in Plymouth, Franconia, Lincoln, Woodstock, and Bethlehem. Using the buildings (a courthouse, a church, a café/store, and a farmhouse) where each group is housed as focal points, the exhibition explores how these five communities developed and continue to evolve.

Special thanks to Marcia Schmidt Blaine for stepping up to help coordinate our efforts.

Lenders for this exhibit include:

- Julie Bernier

- Bethlehem Historical Society

- Clare Brown

- The Caulder Family

- Robert S. Chase and Richard M. Candee Trust

- The Fadden Family

- Dick Flanders

- Franconia Heritage Museum

- Library of Congress

- Fletcher Manley

- The McLane Family

- Michael J. Spinelli, Jr. Center for University Archives and Special Collections at Plymouth State University

- Michael Mooney and Robert Cram

- New Hampshire Broadband

- New Hampshire Historical Society

- Rebecca Blaine Pare

- Plymouth Historical Society

- Emilie Talpin

- Town of Bethlehem

- Town of Woodstock

- Upper Pemigewasset Historical Society

Introduction

How does a place become a community? And how do we sustain our communities over time? This exhibition examines how five communities along the western White Mountains—Plymouth, Lincoln, Woodstock, Franconia, and Bethlehem— evolved into the places they are today. Through collaboration with local historical societies, we illuminate the stories of these rural communities, their challenges, and their perseverance. While each community has its own story, this exhibition explores the threads that bind them together.

Each of these thematic threads is represented by an iconic building—a courthouse, a church, a farmhouse, and a café/store—that serves as both gathering place and symbol of local identity. These structures embody the intersection of people, place, and purpose that defines rural America. Bridging these narratives is Franconia Notch, a geographical feature that has simultaneously divided and united these communities for generations. As you explore this exhibition, consider how the past continues to shape the present and future of these communities at their own crossroads of change.

Structures that Bind

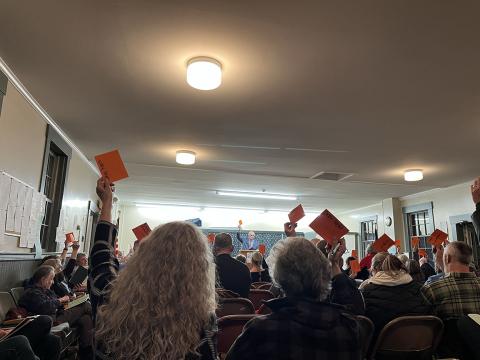

Rural communities forge their identities through formal and informal governance. Town meetings, local committees, and elected officials promote civic engagement while addressing community needs. Now the home of the Plymouth Historical Society, the Old Webster Courthouse, dating to 1774, stands as a testament to democratic governance and the rule of law in northern New Hampshire. Meanwhile, select boards, planning boards, and conservation commissions demonstrate how civic responsibility transcends political differences. These official structures establish frameworks that nurture community relationships, often intersecting with less formal networks of care and mutual aid. Community-wide celebrations, from annual Old Home Days to 250th anniversaries, bring people together for a shared purpose.

When crisis strikes—whether economic downturns, natural disasters, or demographic shifts—these governmental structures provide stability while enabling communities to adapt. As rural populations fluctuate and needs evolve, the challenge remains: how can a town maintain responsive governance while preserving the character that makes each community distinct? The persistence of these structures, despite changing circumstances, reveals how rural communities navigate the tension between tradition and innovation as they work to sustain their civic identities.

The Architecture of Communities

Beyond official institutions, community emerges through shared spaces where relationships flourish. Each town has created a built environment not only to host their gatherings, but also as a physical representation of the common interests of the people. Churches, fairgrounds, schools, and recreation areas serve as more than mere buildings—they embody collective identity and foster belonging.

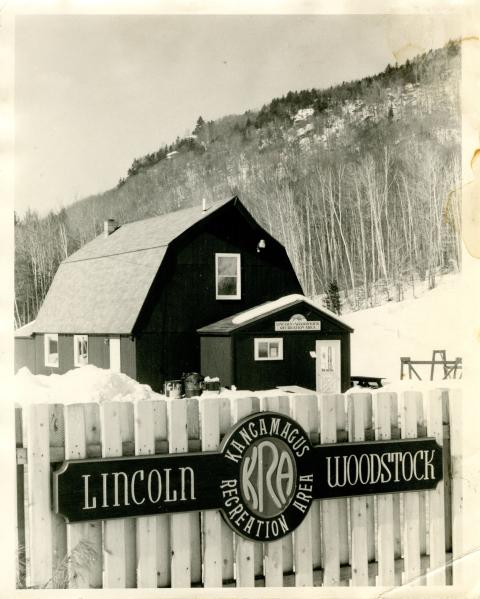

In Lincoln, the Union Church that now houses the Upper Pemigewasset Historical Society once gathered residents weaving faith into the community fabric. As new groups came to the region to work in the woods or in other industries, they built places of worship to foster a sense of community within a new place. Community spaces like the Bethlehem pool and the Kancamagus Recreation Area bring people together around a shared passion for outdoor recreation. Even as digital technologies create virtual gathering spaces, these physical structures remain crucial touchstones of rural identity. Their continued use, adaptation, and preservation illuminate how communities harmonize past with present, transforming architectural heritage into living assets that nurture belonging across generations.

Subsistence and Beyond

Drawn to the western White Mountains by the abundance of timber, families also had to cultivate harsh terrain to sustain themselves. As train service made its way into the mountains in the second half of the nineteenth century, these farming communities discovered a new source of income: tourism. Built by Joel Spooner in 1878, the farmhouse that now contains the Franconia Heritage Museum housed families as well as visitors. Farmers across the region began offering room and board to city dwellers seeking mountain air and scenic beauty. This agricultural hospitality created the foundation for today's tourism industry.

Many historic inns evolved from farmhouses, with families diversifying their income by accommodating travelers. Local products—maple syrup, fresh produce, and handcrafts—cultivated initially for subsistence, became attractions themselves. This interweaving of agriculture and tourism continues today through farm-to-table restaurants, u-pick farms, and farmers' markets. As communities navigate changing economic landscapes, this dual heritage offers a model for sustainability, demonstrating how rural livelihoods can evolve while maintaining connection to the land that first supported these communities.

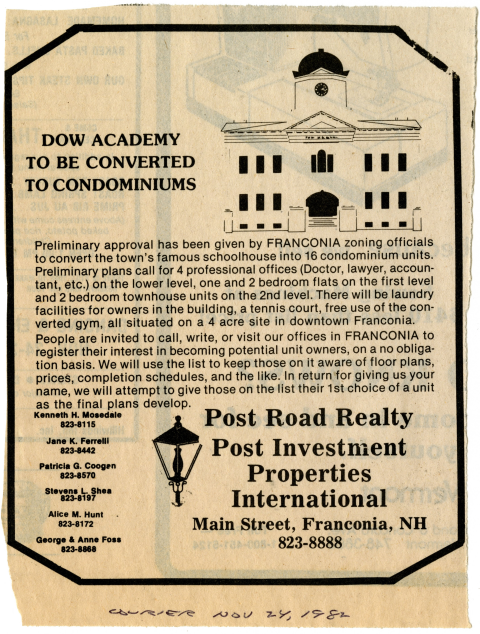

Growth through Renewal

Rural communities persist through continuous reinvention. The building that houses the Bethlehem Historical Society is a case in point: it was built in 1880 as a cafe on the grounds of Ranlet Hotel, was moved down Main Street by oxen to its present location in 1895, where it was a cafe again in its new spot, then a meat market and grocer, then an antique store, then a realtor's office, then a vacant building for a while until it was seized by the town for back taxes, and now the visitor center and historical society.

Facing economic shifts, environmental challenges, and changing demographics, these towns have repeatedly reimagined their futures while honoring their pasts. As residents renovate historic buildings or repurpose abandoned

structures, they're not simply maintaining property—they're cultivating environments where community can thrive. This adaptability emerges across the region, where abandoned mills transform into shopping areas, historic buildings house innovative businesses, and traditional industries adopt sustainable practices.

Such reinvention requires both vision and pragmatism. Communities are constantly developing their distinctive identities while embracing necessary change—preserving what matters most while discarding what no longer serves. This delicate balance between continuity and transformation has enabled these five communities not merely to survive but to flourish through periods of profound transition.

Building Connectivity

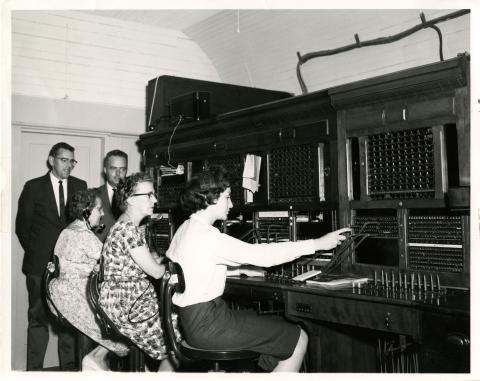

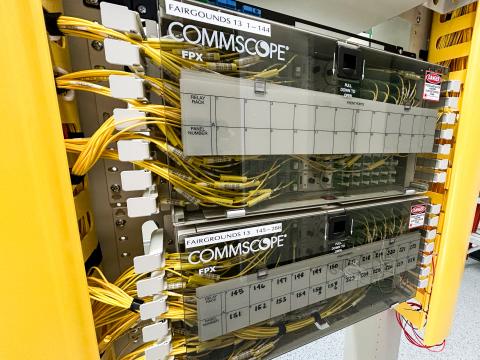

Infrastructure—physical, technological, and social—shapes how communities develop and connect. Early settlers to the region encountered a well-developed network of trails established by Indigenous communities to connect the coastal areas to the mountains. The arrival of the railroad in the 1850s first linked these isolated mountain towns to urban centers, transforming local economies and bringing the first waves of tourism. Roads for cars followed, which knit communities together while showcasing natural beauty. Electricity reached many areas through New Deal rural electrification programs in the 1930s and 1940s, revolutionizing daily life.

Today, broadband access represents the newest infrastructure frontier, with high-speed internet determining which communities can participate fully in the digital economy. Yet infrastructure development always involves choices about what—and whom—to connect. Communities that gained early access to transportation networks often flourished, while others remained isolated longer. These connectivity decisions continue to resonate today, as communities advocate for equitable infrastructure that bridges rather than deepens divides. As these five towns look toward the future, they face crucial questions about developing infrastructure that supports sustainable growth while preserving natural resources.

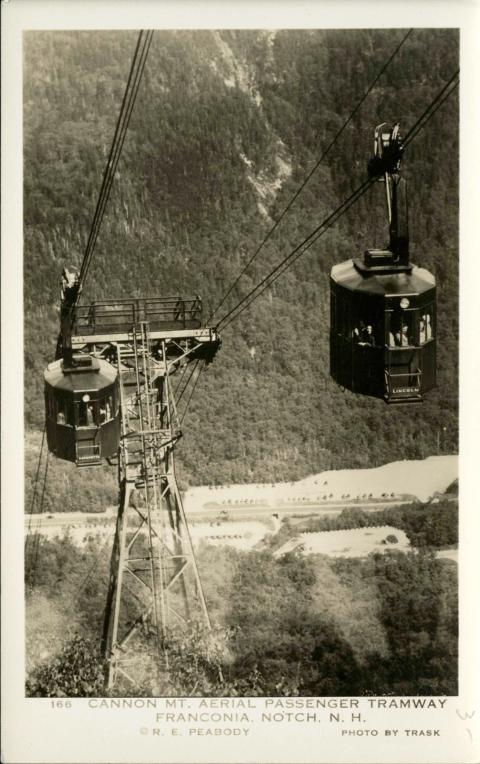

The Allure of the Notch

Franconia Notch stands as both a geological marvel and a cultural touchstone. This dramatic mountain pass has captivated visitors since the early 19th century, when artists and writers sought inspiration in its rugged grandeur. The eight miles of road that stretches between the Flume Gorge in the south and Echo Lake in the north has an incredible concentration of natural wonders. The Old Man of the Mountain—a naturally-formed rock profile that became New Hampshire's enduring symbol—drew generations of travelers until its collapse in 2003. The Notch's powerful presence shaped local identity while launching the region's tourism economy. Grand hotels arose to accommodate wealthy visitors seeking the therapeutic mountain air, and local residents adapted to serve as guides, innkeepers, and storytellers. Beyond recreation, the Notch represents a conservation milestone. The struggle to protect it from over-development continues to influence environmental ethics throughout the region. Even as the physical landscape evolves through natural processes and human intervention, the Notch remains a centerpiece—embodying the relationship between communities and the natural environment that continues to define the western White Mountains.

Connection and Controversy

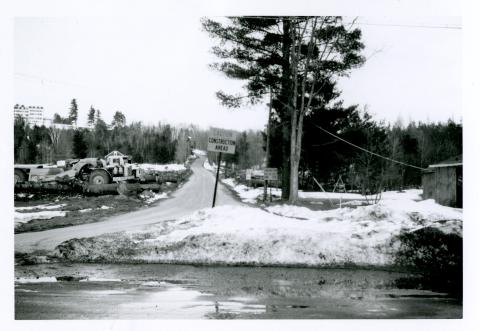

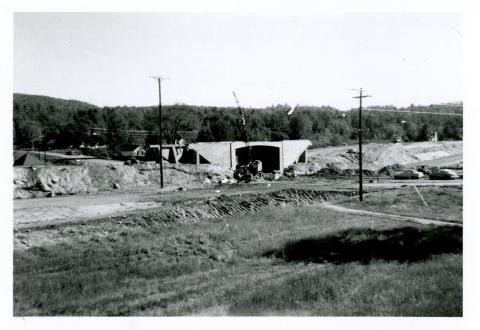

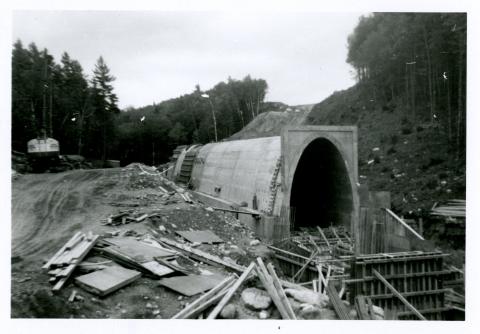

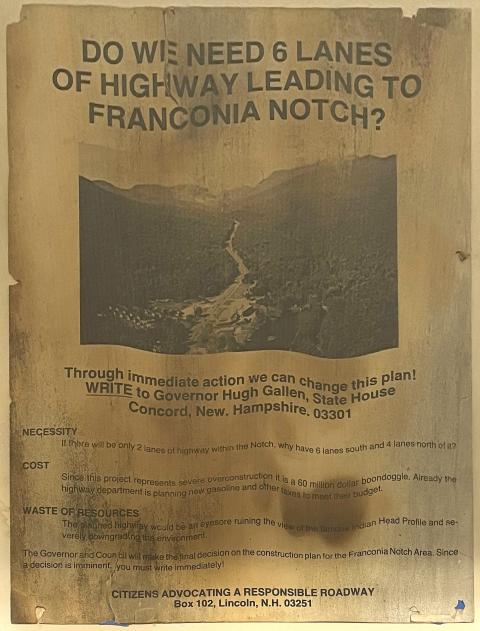

The construction of Interstate 93 through Franconia Notch in the 1970s and 1980s sparked unprecedented debate about progress, preservation, and community values. Advocates argued the highway would bring economic vitality to struggling northern communities by improving access for tourists and commerce. Opponents feared the destruction of natural beauty and ecological damage to one of New Hampshire's most treasured landscapes. The resulting compromise—a unique parkway design with narrower lanes and lower speed limits—represented an innovative balance between development and conservation.

This hard-won solution emerged through community engagement, creative engineering, and willingness to reconsider standard approaches. The Franconia Notch Parkway controversy reverberates today as communities continue to navigate tensions between accessibility and preservation. The parkway stands as testament to how rural places can chart their own paths when faced with external pressures, developing solutions that respect both human needs and natural heritage.

Collecting for Future Storytellers

What will future generations want to know about our communities today? Traditional historical collections often preserve formal records and special occasions, but everyday life—particularly after 1970—remains underrepresented. Digital photographs languish on smartphones, social media captures community events that may never enter archives, and ordinary objects that define contemporary rural life are rarely preserved. What deserves saving for tomorrow's storytellers? How might we document today's community struggles over broadband access, affordable housing, or changing agricultural practices? What artifacts will explain our community's response to climate change or the pandemic?

The historical societies partnering in this exhibition actively collect materials that will enable future exhibitions to tell richer stories about this pivotal era. By consciously preserving the present, we acknowledge that today's ordinary moments become tomorrow's history. We invite you to reflect on what objects or stories from your experience should be preserved to help future generations understand rural life at this crossroads of change.

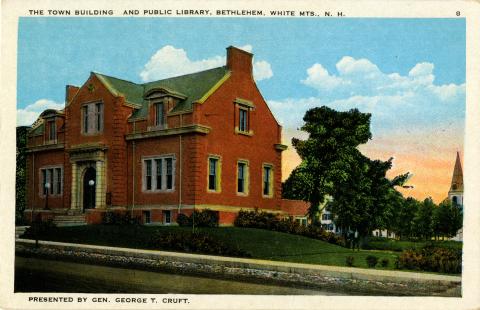

Bethlehem

Bethlehem, the northernmost town in our group, was granted a charter in 1774, but it wasn’t until 1787 that white settlers arrived and settled permanently. The town was incorporated as Bethlehem in 1799; in the 1800 census, 33 farming families lived in town. In the early 19th century, the town served as a vital crossroad for stagecoaches traveling to Crawford Notch and Portland, Maine. By the 1830s, taverns and blacksmith shops lined Main Street, catering to a steady stream of travelers passing through. Farm families supplemented their income by taking in boarders, and tourist houses sprang up to take advantage of Bethlehem’s scenic landscapes and pollen-free air. The railroad came to Bethlehem Junction in 1876. In the same year, the Maplewood Hotel opened. Notable writers found the town to be inspirational: Robert Frost, Henry David Thoreau, Helen Hunt Jackson, among others visited. The automobile changed tourism dynamics. About 1916, Jewish families began arriving in town, often seeking relief from hay fever. Bethlehem became a popular destination for more Jewish families well into the 20th century. The town declined as a popular retreat after antihistamines and air conditioning took away Bethlehem’s draw as an allergy-free destination, and the grand hotels and cottages closed. Today Bethlehem has undergone a transformation: it is a vibrant and diverse cultural community, with a thriving arts scene and award-winning eateries, set against the backdrop of the White Mountains.

Franconia

Franconia received a colonial charter in 1764, but remained unsettled, so a new charter was granted in 1772. The first European settlers in Franconia were German immigrants who moved into the town boundaries in 1773. Franconia’s townspeople developed multiple industries centered around the land around them, including, farming, making starch from potatoes, logging or running sawmills, mining copper, and most famously, smelting iron. The iron works were an early tourist draw. When the Old Man of the Mountain was “discovered” in 1805, it became and remained a notable attraction until it fell off the face of Cannon Mountain in 2003.

By horse, carriage, railroad, or automobile, tourists arrived in town, staying with farm families, in small hotels or the grand Profile House. Robert Frost lived in town for a number of years and wrote several beloved poems there. Franconia Notch State Park was established in 1928, and Cannon Mountain ski resort helped transform the town into a winter sports destination. This popularity continues today and is a major part of Franconia’s identity. Like many small towns, Franconia faces challenges such as balancing economic development with conservation efforts, preserving its cultural heritage, and addressing infrastructure needs. Community engagement is key to ensuring the town’s sustainability and resilience in the future.

Lincoln/Woodstock

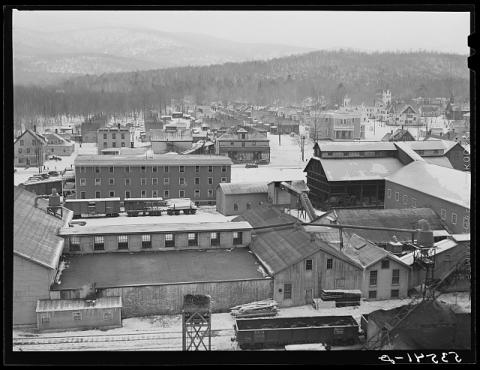

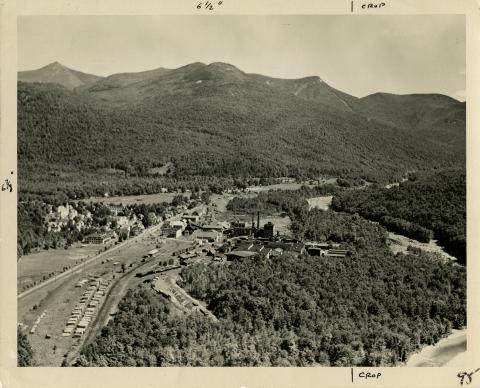

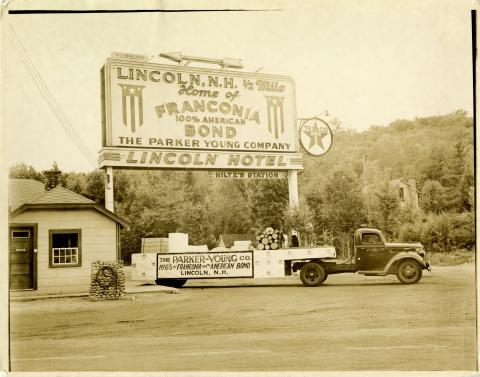

The histories of Lincoln and Woodstock are at once distinct and deeply entwined. While they received their colonial charters within a year of each other (1764 and 1763, respectively), the early histories of the towns diverge. By 1840, there were only 76 people living in Lincoln compared to 472 in Woodstock. At that point there were four sawmills using the Pemigewasset to send logs down to the southern part of the state. After logging magnate J.E. Henry arrived in what would become the village of Lincoln in 1892, its population stabilized and then grew. By 1910 Lincoln had outgrown Woodstock, and it continued to grow following the opening of Parker Young paper mill in 1917.

During the middle of the nineteenth century, tourists discovered the area, especially geological wonders like the Flume and Lost River, and growing numbers of travelers came to the towns, many of them staying in various iterations of the Flume House. Lincoln became a crossroads when the Kancamagus Highway opened in 1959, connecting the east and west notches of the White Mountains. The region’s skiing industry took off in 1966 with the establishment of Loon Mountain under former Governor Sherman Adams.

Today, the two towns are relatively close in size, but whereas Woodstock’s population is spread out along the north-south and east-west roads that pass through town, Lincoln’s population is concentrated in the town center because the vast majority of its land area is in the National Forest. While they share a school and some services, the two towns retain their individual identities.

Plymouth

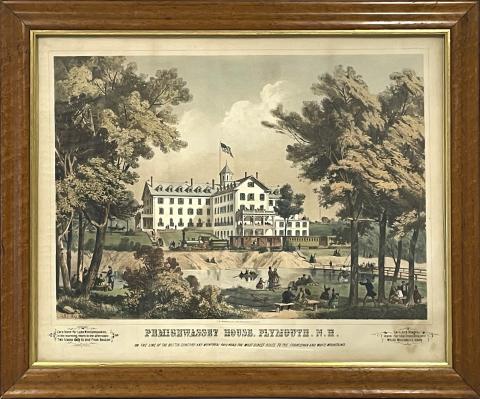

Plymouth sits at multiple crossroads: the confluence of the Pemigewasset and Baker Rivers, the junction of Interstate 93 and Highway 25, and the shifting landscape from the Lakes Region to the mountains. Indigenous peoples took advantage of this area to grow crops in the intervale, fish in the rivers, and trade. White settlers followed and found the same advantages. The town was chartered in July 1763, and, by 1800, the town included 743 people with saw and grist mills, a settled minister, the first roads, and at least one tavern to accommodate people coming to town for the county court sessions or traveling through on business.

While early on agriculture dominated the local economy, Plymouth’s economy diversified over the 19th century with manufacturing, railroad company headquarters, hotels and boarding houses, and a center of higher education. Plymouth was and remains the region’s market town. The population reflects the economic growth and increased steadily throughout its history. The town began to pull in visitors through the railroad traffic: skiers came by train from Boston, people came to see plays and musical events at the college, and tourists arrived to tramp in the nearby mountains. They stayed in local hotels, including the grand Pemigewasset House. Today, the town is at a literal as well as figurative crossroads as townspeople work to balance growth with preservation and local culture.